Portland, Oregon – Copyright attorneys for Jacobus Rentmeester of Westhampton Beach, New York sued for copyright infringement in the District Court of Oregon, Portland Division alleging that Nike, Inc. of Beaverton, Oregon infringed Rentmeester’s copyrighted photo of Michael Jordan. This photo, Registration Number VA0001937374, has been registered with the U.S. Copyright Office.

Rentmeester, a New York photographer, commenced this litigation against Nike for Nike’s use of the iconic “Jumpman” photo in promoting its Jordan brand. In the lawsuit, Plaintiff Rentmeester contends that Nike directly, contributorily, and vicariously infringed his copyrighted image of Michael Jordan.

Rentmeester claims that he created the “Jordan Photo” for inclusion in a 1984 Olympic edition of Life Magazine, as part of a photo essay that he produced for the magazine. Among the athletes featured in Rentmeester’s photo essay, in addition to Jordan, were Carl Lewis and Greg Louganis.

At issue in this litigation is Rentmeester’s Jordan Photo. Rentmeester contends that he “conceived the central creative elements of the photograph.” These elements included portraying Jordan alone against the sky, “soar[ing] elegantly” and in a modified version of a grand jeté, a ballet jump during in which the person performs the splits in midair. According to the complaint, this type of jump was not typical for Jordan.

Rentmeester states that, after his photo was published, he agreed to accept a fee of $150 from Nike for temporary use of the photo for a “slide presentation only, no layouts or any other duplication.”

Nike later paid Rentmeester $15,000 for a limited license to use a modified work, although Plaintiff states that this agreement was reached only after Nike had already begun infringing use of the work and Rentmeester had complained to Nike of copyright infringement. Rentmeester contends that this license was limited to two years of use, on posters and billboards only, and for use within North America only. Rentmeester alleges that Nike exceeded the terms of that limited license by using the modified image other than on posters or billboards as well as outside North America. He also asserts that Nike’s use of the Jordan Photo constitutes willful copyright infringement as of the expiration of the license in 1987.

In the complaint, filed by copyright lawyers for Plaintiff, the following counts are enumerated:

• First Cause of Action: Copyright Infringement

• Second Cause of Action: Vicarious Copyright Infringement

• Third Cause of Action: Contributory Copyright Infringement

• Fourth Cause of Action: Violations of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act

Rentmeester, via his copyright attorneys, asks the court for a judgment of infringement; for an injunction; for impoundment of all infringing works; for actual and statutory damages, including profits attributable to infringement of Rentmeester’s copyright; for punitive damages; for a finding that neither Nike nor any independent infringers can assert copyright protection in any of the infringing works; and for costs and attorneys’ fees.

Indiana Intellectual Property Law News

Indiana Intellectual Property Law News

Fort Wayne, Indiana – A patent and copyright attorney for

Fort Wayne, Indiana – A patent and copyright attorney for

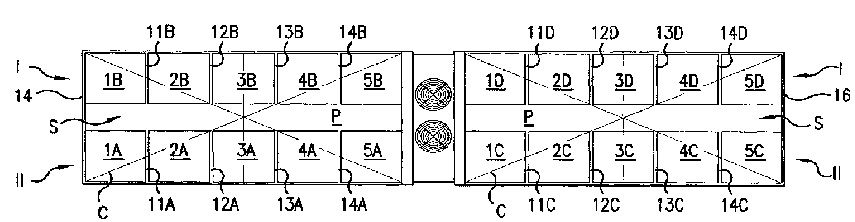

Vincent P. Tippmann Sr. Family, LLC (“Tippmann Family, LLC”) claims ownership of the patent-in-suit, a technology that facilitates rapid and efficient freezing and thawing of food products. It also indicates that it is the inventing and owning company of various patents and patent applications related to apparatuses and methods for blast freezing and/or thawing of products.

Vincent P. Tippmann Sr. Family, LLC (“Tippmann Family, LLC”) claims ownership of the patent-in-suit, a technology that facilitates rapid and efficient freezing and thawing of food products. It also indicates that it is the inventing and owning company of various patents and patent applications related to apparatuses and methods for blast freezing and/or thawing of products. Indianapolis, Indiana filed a lawsuit in the

Indianapolis, Indiana filed a lawsuit in the  eliminating Gulliver’s obligation to pay portions of the settlement amount.

eliminating Gulliver’s obligation to pay portions of the settlement amount.