Indianapolis, Indiana – A trademark attorney for Order Inn, Inc. of Las Vegas, Nevada filed a lawsuit in the Southern District of Indiana alleging that TJ Enterprises of Indiana, LLC d/b/a Order In (“Order In”) and Tom Ganser, both of Carmel, Indiana and other unknown “Doe”  individuals infringed trademarks for “ORDER INN”, Registration Nos. 3,194,903 and 2,801,951, which have been issued by the U.S. Trademark Office.

individuals infringed trademarks for “ORDER INN”, Registration Nos. 3,194,903 and 2,801,951, which have been issued by the U.S. Trademark Office.

Order Inn Hospitality Services, also known as Order Inn, was founded in 2001. The company’s initial core product, Order Inn Room Service, was created to provide room service to guests of limited-service hotels and timeshares. Order Inn states that it has developed partnerships with over 10,000 hotels and 700 restaurants nationwide and that it does business in Indiana.

Order Inn asserts ownership over several registered trademarks for “Order Inn,” among them a registration for “On-line ordering services in the field of restaurant take-out and delivery; on-line order fulfillment services for goods and services which hotel guests, residents or businesses may wish to purchase; promoting the goods and services of others by preparing and placing advertisements in menus placed in hotels, residences or businesses; providing information in the field of on-line restaurant ordering services.”

Order Inn claims that, as a result of its extensive, continuous and exclusive use of the “Order Inn” trademark in connection with its services, that trademark has come to be recognized by consumers as identifying Order Inn’s services as well as distinguishing them from services offered by others. It further claims that its trademark has developed substantial goodwill throughout the United States.

Order In, which also does business in Indiana, facilitates restaurant takeout and delivery through its website and via telephone. Order In is accused of trademark infringement of a registered trademark and false designation of origin. Ganser is alleged to be an owner and/or manager of Order In and to have personally participated in any trademark infringement. Both Order In and Ganser are accused of infringing upon the Order Inn trademark willfully, intentionally and deliberately and with full knowledge and willful disregard of Order Inn’s intellectual property rights.

In its complaint, filed by a trademark lawyer for Order Inn, the following counts are alleged:

• Federal Trademark Infringement Under 15 U.S.C. §1114

• False Designation of Origin and Unfair Competition under 15 U.S.C. §1125(a)

Order Inn asks for an injunction; damages, including treble damages; interest; costs and attorney’s fees

Practice Tip:

The protection afforded to a registered trademark is not exhaustive in scope. Among the limits to its applicability are restrictions based on the type of business to which the trademark pertains. From its website, it appears that Order Inn directs its efforts primarily towards guests at hotels, inns and similar temporary-lodging facilities. In contrast, Order In’s offerings are not similarly limited.

Trademarks protection is also unavailable for generic words that merely describe the goods or services for sale. For example, while “Apple” could be trademarked for use in conjunction with the sale of computers, a company would not be allowed to trademark the term to refer to the sale of apples. Similarly here, Order Inn may have difficulty in showing that it should be allowed to prohibit nationwide the use by anyone else of the generic term “order in.”

Indiana Intellectual Property Law News

Indiana Intellectual Property Law News

Indianapolis, Indiana filed a lawsuit in the

Indianapolis, Indiana filed a lawsuit in the  “STRATOTONE” (the “Stratotone mark”),

“STRATOTONE” (the “Stratotone mark”),  infringed the trademark Noble Roman’s, Registration No.

infringed the trademark Noble Roman’s, Registration No.

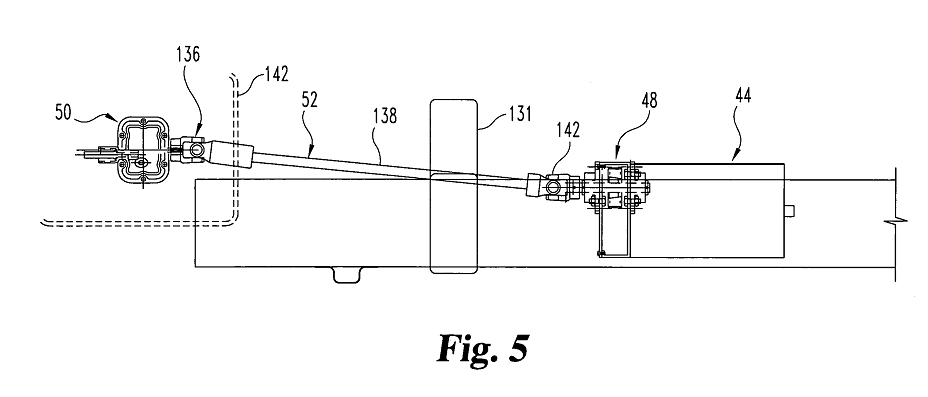

In this lawsuit, Plaintiff Contour Hardening contends that Defendant Vanair has violated, and continues to violate, inter alia, the patent laws of the United States, 35 U.S.C. §§271 and 281- 285, as well as the Federal Trademark Act by infringing Contour Hardening’s two patents, U.S. Patent Nos. 6,979,913 and 7,057,303 (collectively, the “Contour Patents”), and infringing Contour Hardening’s REAL POWER trademark by using Vanair’s allegedly similar ROAD POWER trademark.

In this lawsuit, Plaintiff Contour Hardening contends that Defendant Vanair has violated, and continues to violate, inter alia, the patent laws of the United States, 35 U.S.C. §§271 and 281- 285, as well as the Federal Trademark Act by infringing Contour Hardening’s two patents, U.S. Patent Nos. 6,979,913 and 7,057,303 (collectively, the “Contour Patents”), and infringing Contour Hardening’s REAL POWER trademark by using Vanair’s allegedly similar ROAD POWER trademark. technologies, including fuel systems, controls, air handling, filtration, emission solutions and electrical power generation systems. Cummins employs approximately 46,000 people worldwide and serves customers in approximately 190 countries.

technologies, including fuel systems, controls, air handling, filtration, emission solutions and electrical power generation systems. Cummins employs approximately 46,000 people worldwide and serves customers in approximately 190 countries. Institute’s Project Management Professional (“PMP”) examination and certification process. PMA states that Burch was one of its most-trusted PMP course instructors in the Washington, D.C. area and that, in connection with that position, PMA provided him with access to its proprietary manner of conducting its PMP-examination preparation courses. Moreover, PMA claims that it commissioned Burch and Graywood, Burch’s company, to draft and prepare as a “work for hire” certain training modules that would be for PMA’s exclusive use.

Institute’s Project Management Professional (“PMP”) examination and certification process. PMA states that Burch was one of its most-trusted PMP course instructors in the Washington, D.C. area and that, in connection with that position, PMA provided him with access to its proprietary manner of conducting its PMP-examination preparation courses. Moreover, PMA claims that it commissioned Burch and Graywood, Burch’s company, to draft and prepare as a “work for hire” certain training modules that would be for PMA’s exclusive use.