Terre Haute, Indiana – Copyright attorneys for Union Hospital, Inc. of Terre Haute, Indiana filed an Indiana copyright lawsuit against Attachmate Corporation of Seattle, Washington in the Southern District of Indiana asking the court to declare that Union Hospital had not  infringed either of two Attachmate software works titled “EXTRA!” and “Reflection”, Copyright Registration Nos. TX0005717997 and TX0007351951, which were issued by the U.S. Copyright Office.

infringed either of two Attachmate software works titled “EXTRA!” and “Reflection”, Copyright Registration Nos. TX0005717997 and TX0007351951, which were issued by the U.S. Copyright Office.

Union Hospital, a not-for-profit regional hospital, provides healthcare to residents of the Wabash Valley community, regardless of their ability to pay. Attachmate is one of the largest software companies in the world, with 40 offices doing business in 145 countries.

Union Hospital states that, since at least 1997, it has been licensed to use Attachmate software for which it paid tens of thousands of dollars. In 2013, Attachmate conducted an audit of Union Hospital’s use of Attachmate software products. According to the complaint, as a result of this audit, Attachmate determined that Union Hospital had used the software beyond the terms of the licenses and demanded that Union Hospital pay Attachmate over $2,000,000 in license fees, interest and other charges. Union Hospital indicates Attachmate subsequently threatened to initiate copyright infringement litigation against Union Hospital.

The claims of liability which Attachmate apparently made have been attacked by Union Hospital on several grounds. Union Hospital states that the claim of over-deployment of certain software was based not upon the actual usage of Attachmate’s product, but upon the potential total number of users who could have used Attachmate software on Union Hospital’s server regardless of whether the user ever accessed or used the product. Union Hospital further asserts “estoppel, waiver, laches, and/or acquiescence” in its defense.

This Indiana litigation, filed under the Declaratory Judgment Act, was filed by Indiana copyright lawyers for Union Hospital. The complaint lists three causes of action:

1. Declaratory Judgment on Copyright Infringement Claims

2. Declaratory Judgment on Copyright Infringement Claims for Unregistered Copyrights

3. Declaratory Judgment on Breach of Contract Claims

Union Hospital asks the court to:

a. Declare that one or more of Attachmate’s breach of contract claims are preempted by the Copyright Act;

b. Declare that Attachmate’s asserted license agreements are invalid and unenforceable;

c. Declare that Union Hospital is not liable to Attachmate for copyright infringement, as Union Hospital’s use of Attachmate’s software was licensed;

d. Declare that Attachmate’s copyright infringement and/or breach of contract claims are barred by estoppel, waiver, laches, and/or acquiescence;

e. Declare that Attachmate’s copyright infringement and/or breach of contract claims are barred by the applicable statute(s) of limitations;

f. Declare that, if Attachmate’s claims are allowed to proceed, any damages for Attachmate’s copyright and/or breach of contract claims be substantially reduced due to Attachmate’s failure to mitigate its damages;

g. Declare that Attachmate’s alleged copyrights were not timely registered and therefore Attachmate is barred from seeking statutory damages and attorneys’ fees for its copyright infringement claims;

h. Declare that Attachmate’s copyright infringement claims based on unregistered copyrights are barred; and

i. Alternatively, declare that Attachmate’s is only entitled to de minimis damages because Union Hospital’s uses did not exceed the total number of uses that it contracted for with Attachmate.

Practice Tip:

The use of the compound conjunction “and/or” in this complaint raises some interesting possibilities. As one basis for federal jurisdiction, Plaintiff alleges that “Attachmate’s representatives have expressly or impliedly threatened litigation for breach of contract and/or copyright infringement….” Such an assertion may not be sufficient to invoke federal-question jurisdiction, as it claims that the threat of litigation exists for one of three possible circumstances: breach of contract only, copyright infringement only, or both breach of contract and copyright infringement. Under the first scenario – breach of contract only – no federal jurisdiction would lie. This potential problem may be remedied by other allegations in the complaint, including a separate assertion of diversity jurisdiction.

The use of “and/or” is also found in the prayer for relief. There, Plaintiff asks for, inter alia, declarations “that Attachmate’s copyright infringement and/or breach of contract claims are barred by estoppel, waiver, laches, and/or acquiescence” and “that Attachmate’s copyright infringement and/or breach of contract claims are barred by the applicable statute(s) of limitations.” Again, this use of the compound conjunction leaves open the possibility that the court might interpret the prayer for relief as a request to bar the claims of breach of contract or copyright infringement, but not both.

Continue reading

Indiana Intellectual Property Law News

Indiana Intellectual Property Law News

California d/b/a X-Art.com filed a copyright infringement lawsuit in the

California d/b/a X-Art.com filed a copyright infringement lawsuit in the

New York (“BMI”),

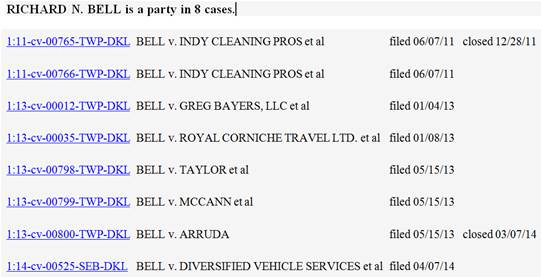

New York (“BMI”),  Defendants are: Diversified Vehicle Services of Marion County, Indiana; Cameron Taylor and Taylor Computer Solutions of Indianapolis, Indiana; Rhonda Williams of Indianapolis, Indiana; Forensic Solutions, Inc. of Waterford, New York; Heath Garrett of Nashville, Tennessee; CREstacom, Inc. of Fishers, Indiana; American Traveler Service Corp LLC, location unknown;

Defendants are: Diversified Vehicle Services of Marion County, Indiana; Cameron Taylor and Taylor Computer Solutions of Indianapolis, Indiana; Rhonda Williams of Indianapolis, Indiana; Forensic Solutions, Inc. of Waterford, New York; Heath Garrett of Nashville, Tennessee; CREstacom, Inc. of Fishers, Indiana; American Traveler Service Corp LLC, location unknown; The

The  of several

of several  infringed either of two Attachmate software works titled “EXTRA!” and “Reflection”, Copyright Registration Nos.

infringed either of two Attachmate software works titled “EXTRA!” and “Reflection”, Copyright Registration Nos.