Richmond, Virginia – PBM Products, LLC (“PBM”) sued Mead Johnson & Company, LLC (“Mead Johnson”) alleging false advertising in violation of the Lanham Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1125(a)(1)(A) and (B), and commercial disparagement. Mead Johnson filed counterclaims against PBM. The district court dismissed the counterclaims and entered an injunction against Mead Johnson. Mead Johnson appealed. The United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit affirmed.

PBM. The district court dismissed the counterclaims and entered an injunction against Mead Johnson. Mead Johnson appealed. The United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit affirmed.

PBM produces store-brand, “generic,” infant formula. Mead Johnson produces baby formula products under the brand name Enfamil, including a standard formula, a formula with broken-down proteins, and a formula with added rice starch. Both companies use the same supplier for two key nutrients–docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and arachidonic acid (ARA)–which are important to an infant’s brain and eye development. Mead Johnson calls these nutrients by their brand name “Lipil,” while PBM describes them generically as “lipids.” Both companies use the same level of the lipids. As a result, PBM includes a comparative advertising label on their formula that states, “Compare to Enfamil.”

PBM sued Mead Johnson under the Lanham Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1125(a), alleging that Mead Johnson engaged in false advertising and commercial disparagement when it distributed more than 1.5 million direct-to-consumer mailers that falsely claimed that PBM’s baby formula products were inferior to Mead Johnson’s baby formula products.

Mead Johnson filed counterclaims against PBM alleging breach of contract, defamation, false advertising, and civil contempt. Mead Johnson’s defamation counterclaim was based primarily on a press release issued by PBM CEO Paul Manning declaring that “Mead Johnson Lies About Baby Formula … Again.” Mead Johnson’s false advertising counterclaim alleged that labels on PBM’s products conveyed several implied messages comparing PBM and Mead Johnson’s formulas. Mead Johnson’s breach of contract and civil contempt counterclaims related to prior litigation between the parties.

Mead Johnson filed counterclaims against PBM alleging breach of contract, defamation, false advertising, and civil contempt. Mead Johnson’s defamation counterclaim was based primarily on a press release issued by PBM CEO Paul Manning declaring that “Mead Johnson Lies About Baby Formula … Again.” Mead Johnson’s false advertising counterclaim alleged that labels on PBM’s products conveyed several implied messages comparing PBM and Mead Johnson’s formulas. Mead Johnson’s breach of contract and civil contempt counterclaims related to prior litigation between the parties.

After a jury found that Mead Johnson had engaged in false advertising, the district court issued an injunction prohibiting Mead Johnson from making similar claims, which enjoined all four advertising claims that Mead Johnson had made, including the express claim that “only Enfamil LIPIL is clinically proven to improve brain and eye development.”

On appeal, Mead Johnson presented three clusters of issues for review by the Fourth Circuit: (1) whether the district court erred in its dismissal of Mead Johnson’s counterclaims; (2) whether the district court abused its discretion in its admission of expert opinion testimony and evidence of prior litigation between the parties; and (3) whether the district court erred or abused its discretion in issuing the injunction.

The dismissals of Mead Johnson’s counterclaims for breach of contract, defamation, false advertising, and civil contempt were all affirmed. The allegedly defamatory statement “Mead Johnson Lies About Baby Formula … Again” was held to be true, as it was found that Mead Johnson had made false statements prior to the publication of PBM’s press release (“Mead Johnson Lies”) and had also made previous false statements about PBM’s baby formula (the “Again” portion of the PBM’s press release). The dismissal of the defamation claim on summary judgment was held to be proper as no false statement had been made.

The Fourth Circuit then upheld the district court’s disposal of Mead Johnson’s Lanham Act counterclaims as a matter of law. Those claims accruing prior to the two-year statute of limitations were affirmed to be time-barred. Claims accruing after that period were affirmed as correctly estopped under the equitable principle of laches.

The Fourth Circuit also held that the district court did not err in granting judgment as a matter of law on Mead Johnson’s Lanham Act counterclaim concerning PBM’s rice starch formula advertisements, holding that the district court had properly concluded that, because the consumer surveys that had been conducted by Mead Johnson had failed to address the allegations in the lawsuit, no relevant evidence had been produced by Mead Johnson on this claim. Moreover, it was held that Mead Johnson had failed to show either falsity of the statements or that any damage was caused by any of the “compare to Enfamil” language that had been used by PBM.

The appellate court then addressed Mead Johnson’s contention that the district court erred by admitting (1) expert survey evidence and (2) evidence of prior Lanham Act litigation between the parties. These decisions were reviewed for abuse of discretion.

Mead Johnson had argued that the survey evidence offered by PBM should be excluded as the consumers involved in the survey did not exactly match the “universe” of consumers appropriate to this litigation. The district court was not convinced. It noted that “while Mead Johnson has pointed out numerous ways in which it would have conducted [the] survey differently, its arguments do not demonstrate that the methods used were not of the type considered reliable by experts . . . .” The district court concluded that the possibility that the survey had targeted the wrong universe went to the weight to be accorded to the survey, not to its admissibility. The appellate court cited a Seventh Circuit case, AHP Subsidiary Holding Co. v. Stuart Hale Co., which noted that “[w]hile there will be occasions when the proffered survey is so flawed as to be completely unhelpful to the trier of fact and therefore inadmissible, such situations will be rare” and affirmed the district court’s conclusion “without difficulty.”

Mead Johnson also had also asserted that the district court had erred in admitting evidence of the 2001 and 2002 Lanham Act lawsuits filed by PBM, contending that the evidence was irrelevant and more prejudicial than probative. The Fourth Circuit found that the history of prior litigation was both relevant and that its probative value was not substantially outweighed by any danger of unfair prejudice. Moreover, in upholding the trial court’s ruling, the appellate court opined that a district court’s decision to admit evidence over an objection based on the potential for unfair prejudice “will not be overturned except under the most extraordinary circumstances, where [the district court’s] discretion has been plainly abused.”

The Fourth Circuit then turned to Mead Johnson’s contention that the injunction issued by the district court had been improper. Mead Johnson argued that the injunction was improper for two reasons. First, it asserted that PBM failed to establish any risk of recurrence of the violation. Second, it argued that the scope of the injunction was too broad, as it prohibited conduct that PBM had not proved at trial and that it was beyond the harm PBM sought to redress.

The appellate court was not persuaded. At trial, the jury had returned a verdict in favor of PBM on its false advertising claim and had awarded PBM $13.5 million in damages. In such a case, where a violation has been established and the party seeking the injunction has made a showing that such an injunction is proper, section 1116(a) of the Lanham Act vests district courts with the “power to grant injunctions, according to the principles of equity and upon such terms as the court may deem reasonable, to … prevent a violation under [§ 1125(a) of the Lanham Act].” The Fourth Circuit held that a showing sufficient to support the district court’s injunction had been made and upheld the lower court’s ruling. The appellate court further indicated that the injunction was proper as, “PBM cannot fairly compete with Mead Johnson unless and until Mead Johnson stops infecting the marketplace with misleading advertising.”

Finally, Mead Johnson argued that, because the general jury verdict did not specify which of the four statements in the mailer the jury found to be false and/or misleading, the district court’s injunction must be limited only to the mailer or other advertisements not colorably different from the mailer. The Fourth Circuit rejected the narrow construction suggested by Mead Johnson. It noted again that, inter alia, Mead Johnson’s claim that it was the “only clinically proven” formula had been found to be misleading by the district court. It concluded that because the district court’s interpretation of the jury verdict was plausible in light of the record viewed in its entirety, the factual findings upon which it based the scope of its injunction could not as a matter of law be clearly erroneous. Consequently, the scope of the injunction also was affirmed.

Practice Tip #1: These parties are familiar combatants on the Lanham Act battlefield. For example, in 2001, Mead Johnson distributed brochures and tear-off notepads to patients in pediatricians’ offices stating that store-brand formula did not have sufficient calcium or folic acid. PBM sued and obtained a restraining order prohibiting Mead Johnson from making similar statements. The parties settled that dispute. Then, in 2002, Mead Johnson distributed a chart to physicians stating that store-brand formula did not contain beneficial nucleotides. PBM sued and, again, the parties settled.

Practice Tip #2: The Lanham Act prohibits the “false or misleading description of fact, or false or misleading representation of fact, which … in commercial advertising or promotion, misrepresents the nature, characteristics, qualities, or geographic origin of his or her or another person’s goods, services, or commercial activities.” 15 U.S.C.A. § 1125(a)(1)(B).

Practice Tip #3: In the Seventh Circuit, as with other federal circuits, “[A] court may find on its own that a statement is literally false, but, absent a literal falsehood, may find that a statement is impliedly misleading only if presented with evidence of actual consumer deception.” Abbott Labs. v. Mead Johnson & Co., 971 F.2d 6, 14 (7th Cir. 1992).

Practice Tip #4: Before an injunction may issue, the party seeking the injunction must demonstrate that (1) it has suffered an irreparable injury; (2) remedies available at law are inadequate; (3) the balance of the hardships favors the party seeking the injunction; and (4) the public interest would not be disserved by the injunction. eBay, Inc. v. MercExchange, 547 U.S. 388, 391 (2006).

Continue reading

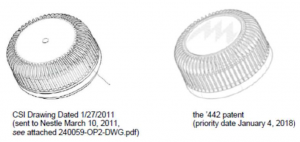

Indianapolis, Indiana –The Plaintiff, BTL Industries, Inc. filed suit against Defendant, JV Medical Supplies, Inc. for trademark infringement, false advertising and patent infringement.

Indianapolis, Indiana –The Plaintiff, BTL Industries, Inc. filed suit against Defendant, JV Medical Supplies, Inc. for trademark infringement, false advertising and patent infringement. Indiana Intellectual Property Law News

Indiana Intellectual Property Law News

PBM. The district court dismissed the counterclaims and entered an injunction against Mead Johnson. Mead Johnson appealed. The

PBM. The district court dismissed the counterclaims and entered an injunction against Mead Johnson. Mead Johnson appealed. The  Mead Johnson filed counterclaims against PBM alleging breach of contract, defamation, false advertising, and civil contempt. Mead Johnson’s defamation counterclaim was based primarily on a press release issued by PBM CEO Paul Manning declaring that “Mead Johnson Lies About Baby Formula … Again.” Mead Johnson’s false advertising counterclaim alleged that labels on PBM’s products conveyed several implied messages comparing PBM and Mead Johnson’s formulas. Mead Johnson’s breach of contract and civil contempt counterclaims related to prior litigation between the parties.

Mead Johnson filed counterclaims against PBM alleging breach of contract, defamation, false advertising, and civil contempt. Mead Johnson’s defamation counterclaim was based primarily on a press release issued by PBM CEO Paul Manning declaring that “Mead Johnson Lies About Baby Formula … Again.” Mead Johnson’s false advertising counterclaim alleged that labels on PBM’s products conveyed several implied messages comparing PBM and Mead Johnson’s formulas. Mead Johnson’s breach of contract and civil contempt counterclaims related to prior litigation between the parties.