Indianapolis, Indiana – An Indiana patent attorney for Eli Lilly and Company (“Lilly”) of Indianapolis, Indiana filed an intellectual property lawsuit in the Southern District of Indiana alleging that Fresenius Kabi USA, LLC (“Fresenius”) of Lake Zurich, Illinois infringed the patented product ALIMTA®, Patent No. 7,772,209, which has been registered by the U.S. Patent Office.

Lilly is engaged in the business of research, development, manufacture and sale of pharmaceutical products worldwide. Fresenius is in the business of manufacturing, marketing, and selling generic drug products.

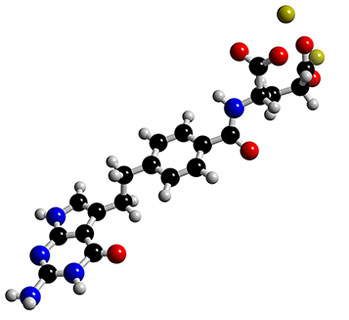

ALIMTA, which is licensed to Lilly, is a chemotherapy agent used for the treatment of various types of cancer. ALIMTA is composed of the pharmaceutical chemical pemetrexed disodium. It is indicated, in combination with cisplatin, (a) for the treatment of patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma, or (b) for the initial treatment of locally advanced or metastatic nonsquamous non-small cell lung cancer. The drug is also indicated as a single agent for the treatment of patients with locally advanced or metastatic nonsquamous non-small cell lung cancer after prior chemotherapy. Additionally, ALIMTA is used for maintenance treatment of patients with locally advanced or metastatic nonsquamous non-small cell lung cancer whose disease has not progressed after four cycles of platinum-based first-line chemotherapy. One or more claims of U.S. Patent No. 7,772,209 (“the ‘209 patent”) cover a method of administering pemetrexed disodium to a patient in need thereof that also involves administration of folic acid and vitamin B12.

This Indiana patent infringement lawsuit arises out of the filing by Defendant Fresenius of an Abbreviated New Drug Application (“ANDA”) with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (“FDA”) seeking approval to manufacture and sell generic versions of ALIMTA prior to the expiration of the ‘209 patent. Fresenius included as a part its ANDA filing a certification of the type described in Section 505(j)(2)(A)(vii)(IV) of the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act, 21 U.S.C. § 55(j)(2)(A)(vii)(IV), with respect to the ‘209 patent, asserting that the claims of the ‘209 patent are invalid, unenforceable, and/or not infringed by the manufacture, use, offer for sale, or sale of Fresenius’ ANDA products.

In its patent infringement complaint, filed by an Indiana patent lawyer, Lilly states that Fresenius intends to engage in the manufacture, use, offer for sale, sale, marketing, distribution, and/or importation of Fresenius’ ANDA Products and the proposed labeling therefor immediately and imminently upon approval its ANDA filing, i.e., prior to the expiration of the ‘209 patent. Lilly asserts that Fresenius’ actions constitute and/or will constitute infringement of the ‘209 patent, active inducement of infringement of the ‘209 patent, and contribution to the infringement by others of the ‘209 patent.

Lilly asserts that, in a prior case, 10-cv-1376-TWP-DKL, the court rejected Fresenius’ challenges to the validity of certain claims of the ‘209 patent. Accordingly, states Lilly, Fresenius should be estopped from challenging the validity of those claims of the ‘209 patent in the instant litigation.

Lilly lists a single count in this lawsuit – Infringement of U.S. Patent No. 7,772,209 – and asks the court for:

a) A judgment that Fresenius has infringed the ‘209 patent and/or will infringe, actively induce infringement of, and/or contribute to infringement by others of the ‘209 patent;

b) A judgment ordering that the effective date of any FDA approval for Fresenius to make, use, offer for sale, sell, market, distribute, or import Fresenius’ ANDA Product, or any product the use of which infringes the ‘209 patent, be not earlier than the expiration date of the ‘209 patent, inclusive of any extension(s) and additional period(s) of exclusivity;

c) A preliminary and permanent injunction enjoining Fresenius, and all persons acting in concert with Fresenius, from making, using, selling, offering for sale, marketing, distributing, or importing Fresenius’ ANDA Product, or any product the use of which infringes the ‘209 patent, or the inducement of or contribution to any of the foregoing, prior to the expiration date of the ‘209 patent, inclusive of any extension(s) and additional period(s) of exclusivity;

d) A judgment declaring that making, using, selling, offering for sale, marketing, distributing, or importing of Fresenius’ ANDA Product, or any product the use of which infringes the ‘209 patent, prior to the expiration date of the ‘209 patent, infringes, will infringe, will actively induce infringement of, and/or will contribute to the infringement by other of the ‘209 patent;

e) A declaration that this is an exceptional case and an award of attorneys’ fees pursuant to 35 U.S.C. § 285; and

f) An award of Lilly’s costs and expenses in this litigation.

Continue reading

Indiana Intellectual Property Law News

Indiana Intellectual Property Law News