Indianapolis, IN – Patent lawyers for Boston Scientific Corporation of Natick, Massachusetts and its wholly-owned subsidiaries, Guidant LLC of Indianapolis, Indiana and Cardiac Pacemakers LLC of St. Paul, Minnesota, filed a lawsuit seeking a declaratory judgment that they have not infringed Patent No. 4,407,288, IMPLANTABLE HEART STIMULATOR AND STIMULATION METHOD, which has been issued by the US Patent Office. The patent lawsuit has been filed against Mirowski Family Ventures, LLC of the State of Maryland.

The patent in question is described as “a method of treating heart arrhythmia with a therapy referred to as ‘cardioversion’ administered by Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator devices.” According to the complaint, Guidant obtained an exclusive license of the patent in question from Mirowski in 1973, which was renewed 2004. Pursuant the license agreement, Guidant was to pay a percentage of sales made based on the patented technology. In 2002, the Southern District of Indiana declared the ‘288 patent invalid in Cardiac Pacemaker, Inc. v. St. Jude Medical, Inc., No. IP 96-1718-C H/G (S.D. Ind.). This patent invalidity determination, however, was overturned by the Federal Circuit Court and then subject to further litigation, which concluded in 2010. Guidant and Mirowski had agreed to suspend payments on the license agreement while during this litigation, and Guidant, in its complaint, states that it has now paid what is due under the license agreement. According to the complaint, Mirowski has sent letters to Guidant accusing Guidant of breaching the license agreement and patent infringement. Boston Scientific and Guidant seek a declaratory judgment of noninfringement, a declaratory judgment of satisfaction of royalty obligation, and a declaratory judgment of no breach of contract.

Continue reading

Articles Posted in Patent Infringement

Knauf Insulation Limited and Knauf Insulation GMBH Sue Certainteed Corporation for Patent Infringement of Insulation Technology

Indianapolis, IN – Patent lawyers for Knauf Insulation Limited of St. Helens, Merseyside, United Kingdom and Knauf Insulation GMBH of Shelbyville, Indiana, filed a patent infringement suit alleging Certainteed Corporation of Valley Forge, Pennsylvania infringed Patent No. 7,854,980, FORMALDEHYDE-FREE MINERAL FIBRE INSULATION PRODUCT, which has been issued by the US Patent Office.

Patent attorneys for Knauf Insulation Limited filed a nearly identical lawsuit against Certainteed in February, which was reported on by Indiana Intellectual Property Law News. According to PACER records, in April Certainteed filed a motion to dismiss for lack of subject matter jurisdiction claiming that Knauf Insulation Limited did not own the asserted patent. Certainteed claimed that Knauf Insulation Limited had transferred all its interest in the patent to Knauf GMBH of Indiana. As of the date that the new lawsuit was filed, the court had not ruled on Certainteed’s motion to dismiss. In the new lawsuit that was filed by Knauf’s patent attorney on May 19, Knauf asserts essentially identical claims and adds Knauf Insulation GMBH of Shelbyville as a plaintiff.

This case has been assigned to Judge Sarah Evans Barker and Magistrate Judge Debra McVicker Lynch in the Southern District of Indiana, and assigned Case No. 1:11-CV-00680-SEB-DML.

Practice Tip: It appears that Knauf is seeking to move this controversy forward without waiting for the court to decide Certainteed’s motion to dismiss for lack of subject matter jurisdiction in the previously filed suit and any potential appeals of this decision. Knauf’s new complaint may be an attempt to fix the perceived problem with the previously filed suit. Knauf has alleged that the ongoing alleged infringement continues to cause it damages and is seeking an injunction. Knauf, therefore, appears to desire a speedy resolution on the merits of the infringement claim.

Continue reading

Brandon S. Judkins Sues Polo Ralph Lauren Corporation for Design Patent Infringement of Table

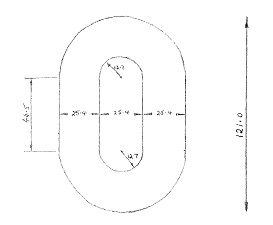

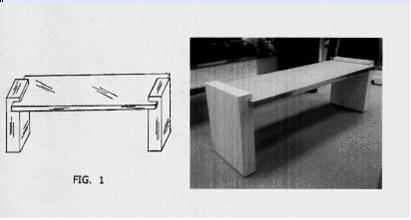

Indianapolis, IN – Brandon S. Judkins of Indianapolis, Indiana filed a patent infringement suit alleging Polo Ralph Lauren Corporation of New York, New York infringed Patent No. D591,090, FURNITURE ARTICLE, which has been issued by the US Patent Office. The patent in question is a design patent of a table.

The complaint alleges that Polo Ralph Lauren is importing, making, using, selling or offering for sale tables that infringe Mr. Judkin’s patent. Specifically, Mr. Judkins alleges that he has seen infringing tables at Macey’s and Carson Pirie Scott locations in Indianapolis. The complaint states that Polo Ralph Lauren is using the tables to display apparel at the stores. Mr. Judkins, an attorney, is representing himself in this case. Mr. Judkins seeks an injunction, declaratory judgment, damages, and costs.

This case has been assigned to Chief Judge Richard L. Young and Magistrate Judge Debra McVicker Lynch in the Southern District of Indiana, and assigned Case No. 1:11-cv-00661-RLY-DML.

Practice Tip: In 2008, the Federal Circuit clarified the test for infringement of design patents in Egyptian Goddess, Inc. v. Swisa, Inc., 543 F.3d 665 (Fed. Cir. 2008). In that case, the court adopted the “ordinary observer” test to replace the “point of novelty” test. In the complaint here, the patented design appears to be pretty basic. The plaintiff may face an uphill battle.

Continue reading

Tissue Extraction Devices, LLC Sues Hologic, Inc. and Suros Surgical Systems, Inc. for Patent Infringement of Breast Biopsy Device

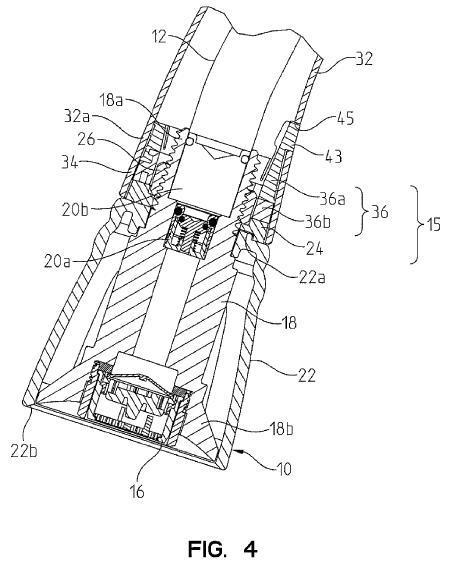

Indianapolis, IN – Patent lawyers for Tissue Extraction Devices, LLC of Indianapolis, Indiana filed a patent infringement suit alleging Hologic, Inc. of Bedford, Massachusetts and Suros Surgical Systems, Inc. of Indianapolis, Indiana infringed Patent No. 7,749,172, PNEUMATIC CIRCUIT, which has been issued by the US Patent Office.

The patent infringement complaint alleges that Jeff Schwindt, owner of Tissue Extraction Devices, invented the technology at issue, which is apparently a hand-piece used by doctors who are performing breast biopsies. Mr. Schwindt assigned the patent rights to Tissue Extraction Devices. The hand-piece allows the doctors to remove a tissue sample for biopsy. According to the complaint, Schwindt worked together with Suros to further develop the hand-piece. Schwindt, however, is the owner of the patent on the hand-piece. Suros introduced breast biopsy systems that included the hand-piece to the market under the names ATEC and EVIVA. Suros is a wholly owned subsidiary of Hologic. Tissue Extraction claims these two systems infringe upon the patent owned by Schwindt. Tissue Extraction’s patent infringement attorneys have requested a declaratory judgment that the patent has been infringed, damages, and attorney fees.

This case has been assigned to Judge Tanya Walton Pratt and Magistrate Judge Tim A. Baker in the Southern District of Indiana, and assigned case no. 1:11-cv-00628-TWP-TAB.

Practice Tip: Based on the complaint, this lawsuit appears to be the result of a dispute between an inventor and another party who participated in some way in the development or marketing of the invention. This case illustrates the importance of having a clear agreement regarding intellectual property rights before parties begin working together to invent, develop and market a product.

Continue reading

Eli Lilly & Co. Wins Court Ruling to Prevent Release of Generic Cymbalta Until Patent Expiration

Indianapolis, Indiana – Patent attorneys for Eli Lilly & Company of Indianapolis successfully blocked the release of generic versions of the anti-depression drug Cymbalta until the expiration of Lilly’s patent for the drug. Last week, Judge Tonya Walton Pratt of the Southern District of Indiana entered an order blocking eight competitor drug companies from releasing their generic versions of Cymbalta until Lilly’s patent expires. Lilly had been involved in this patent infringement lawsuit since 2008. The competitor drugs companies must also agree to notify the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) that they will not seek approval for their generic drugs until Lilly’s patent expires. The patent at issue, Patent No. 5,023,269, which has been issued by the US Patent Office, is due to expire in June 2013, but may be extended.

According to the Indianapolis Business Journal, Lilly reported $2.77 billion in U.S. sales of Cymbalta in 2010. Lilly faces the expiration of several important revenue-generating patents in the next few years, including Cymbalta, Zyprexia, and Humalog.

The case was Eli Lilly & Company v. Wockhardt Limited et al., case number 1:08-cv-1547-TWP-TAB in the Southern District of Indiana before Judge Tanya Walton Pratt

Court Refuses to Strike Expert’s Report in Patent Infringement Case

Indianapolis, Indiana – In a patent infringement case, Judge Jane Magnus-Stinson of the Southern District of Indiana has denied defendants’ request to strike the report of an expert that the plaintiff had attached to a brief. The expert’s report contained a “readily-available summary of the infringement allegations.” The defendants had cited Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(f) as grounds to strike the expert’s report. The court in its order, however, noted that the Rule cited only applied to pleadings, not briefs, and therefore, was inapplicable. Furthermore, the court noted that the plaintiff had submitted the report for a limited purpose and “The Court will, therefore, only consider the report for that limited purpose, and only to the extent authorized by Federal Circuit precedent.”

This is a patent infringement case involving industrial wood veneer technology. The patent litigation attorneys of Overhauser Law Offices, the publisher of this site, represent Capital Machine Company in this litigation. The Indiana Intellectual Property Law and News Blog has previously blogged about the case. There are six patents at issue, all of which have been issued by the US Patent Office:

5,562,137 Method and Apparatus for Retaining a Flitch for Cutting

5,694,995 Method and Apparatus for Preparing a Flitch for Cutting

5,701,938 Method and Apparatus for Retaining a Flitch for Cutting

5,819,828 Method and Apparatus for Preparing a Flitch for Cutting

5,678,619 Method and Apparatus for Cutting Veneer from a Tapered Flitch

7,395,843 Method and Apparatus for Retaining a Flitch for Cutting

The Case No. is 1:09-cv-00702-JMS-DML, and the Order is below.

Continue reading

Simon Property Group and NorthMobileTech Embroiled in Patent Controversy Over Mobile Application For Mall Marketing

Indianapolis, IN – Patent lawyers for Simon Property Group of Indianapolis, Indiana filed a patent lawsuit against NorthMobileTech of Middleton, Wisconsin. In its complaint, Simon states that NorthMobileTech has accused Simon of infringing NorthMobileTech’s patent, and Simon believes a patent infringement lawsuit against it is imminent. On April 20, 2011, the same day as Simon’s patent attorneys filed its suit, patent attorneys for NorthMobileTech filed a patent infringement lawsuit against Simon in the Western District of Wisconsin.

Continue reading

Hill-Rom Services, Inc. Sues Stryker Corporation for Patent Infringement of Beds and Stretchers With Powered Wheels Technology

Indianapolis; IN – Patent lawyers for Hill-Rom Services, Inc. of Batesville, Indiana filed a patent infringement suit alleging Stryker Corporation of Kalamazoo, Michigan infringed twelve patents owned by Hill-Rom all of which have been issued by the US Patent Office.

Hill-Rom alleges that Stryker has manufactured, used , imported, offered for sale, or sold ten types of stretchers and hospital beds with powered wheels that infringe Hill-Rom’s patents. Hill-Rom is seeking damages and declaratory judgment for these patent infringement claims as provided by the Patent Act. In the complaint, patent attorneys also claim that two of Stryker’s patents interfere with patent claims in Hill-Rom’s patents, which were filed with the US Patent Office before Stryker filed its patents. Hill-Rom is seeking a declaratory judgment that Stryker’s infringing patents are invalid.

Masco Corporation of Indiana Sues Sir Faucet, LLC for Patent Infringement of Magnetic Coupling for Faucets

Indianapolis, IN – Patent lawyers for Masco Corporation of Indiana of Indianapolis, IN filed a patent infringement suit alleging Sir Faucet, LLC of Toledo, OH infringed Patent No. 7,753,079, MAGNETIC COUPLING FOR SPRAYHEADS, and Patent No. 7,909,061, MAGNETIC COUPLING FOR SPRAYHEADS, which have been issued by the US Patent Office. Masco does business under the name Delta, and is a fairly frequent litigant in patent infringement lawsuits. Another Masco lawsuit in Indiana is discussed on this site here. Also, Masco was recently sued for patent infringement by one of its major competitors, Moen. That complaint is here. Given that Moen and Sir Faucet suits were filed at about the same time, and that Sir Faucet is located in Northern Ohio where Moen is located, there may be some connection between these two suits.

Indianapolis, IN – Patent lawyers for Masco Corporation of Indiana of Indianapolis, IN filed a patent infringement suit alleging Sir Faucet, LLC of Toledo, OH infringed Patent No. 7,753,079, MAGNETIC COUPLING FOR SPRAYHEADS, and Patent No. 7,909,061, MAGNETIC COUPLING FOR SPRAYHEADS, which have been issued by the US Patent Office. Masco does business under the name Delta, and is a fairly frequent litigant in patent infringement lawsuits. Another Masco lawsuit in Indiana is discussed on this site here. Also, Masco was recently sued for patent infringement by one of its major competitors, Moen. That complaint is here. Given that Moen and Sir Faucet suits were filed at about the same time, and that Sir Faucet is located in Northern Ohio where Moen is located, there may be some connection between these two suits.

While the Indiana suit contains a boilerplate allegation “upon information and belief” that Sir Faucet is “making using, importing, selling, or offering for sale in the United States, including the Southern District of Indiana, products and/or services embodying the patent inventions,” it lacks the type of supporting detail that may be required to prove personal jurisdiction. The complaint also alleges in paragraph 12 that the case is “exceptional,” but states no fact to support this conclusion. If a court finds a case to be “exceptional,” it may award a prevailing party treble damages and attorney’s fees.

Practice Tip: If a defendant is selling an infringing product in the jurisdiction where a plaintiff desires to file a suit, it is helpful to make a representative purchase in that jurisdiction, and reference the sale in the Complaint. This may thwart an attempt by the defendant to have the case dismissed or transferred to the defendant’s preferred venue.

This case has been assigned to Judge Sarah Evans Barker and Magistrate Judge Debra McVicker Lynch in the Southern District of Indiana, and assigned case no. 1:11-cv-00404-SEB-DML.

FC Patents LLC v. Ford Meter Box Company Inc Patent Infringement Case Transferred to Northern District of Indiana from South Carolina

South Bend, IN – The U.S. District Court of South Carolina has transferred a patent infringement case to Northern District Court of Indiana. The transfer comes after the South Carolina District Court granted the defendant’s motion to transfer the case. Ford Meter Box had moved to dismiss the complaint pursuant Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(1) and had asked for transfer to the Northern District of Indiana pursuant 28 U.S.C. § 1404(a) in the alternative.

Continue reading

Indiana Intellectual Property Law News

Indiana Intellectual Property Law News