Washington, D.C. – The United States Supreme Court unanimously affirmed a Sixth Circuit  ruling that intellectual property lawyers for defendant Static Control Components, Inc. of Sanford, North Carolina had properly pled a counterclaim for false advertising under the Lanham Act against Lexmark International, Inc. of Lexington, Kentucky. The Court held that a Lanham Act claim under §1125(a) may be asserted by plaintiffs who are within the zone of interests protected by the Lanham Act and whose injury was proximately caused by a violation of that statute.

ruling that intellectual property lawyers for defendant Static Control Components, Inc. of Sanford, North Carolina had properly pled a counterclaim for false advertising under the Lanham Act against Lexmark International, Inc. of Lexington, Kentucky. The Court held that a Lanham Act claim under §1125(a) may be asserted by plaintiffs who are within the zone of interests protected by the Lanham Act and whose injury was proximately caused by a violation of that statute.

Lexmark sells both printers and toner cartridges for those printers. In addition to selling new Lexmark-branded toner cartridges, it refurbishes used Lexmark cartridges. Those refurbished products are sold in competition with the new cartridges. To hinder others from reusing its cartridges, Lexmark includes a microchip that disables an empty cartridge until Lexmark replaces the chip. Respondent Static Control, a maker and seller of components for the remanufacture of Lexmark cartridges, developed a microchip that enabled empty Lexmark cartridges to be refilled and used again.

Lexmark sued for both copyright infringement and patent infringement. It also informed Static Control’s customers that Static Control had infringed its patents. Static Control counterclaimed, alleging that Lexmark had engaged in false or misleading advertising in violation of §43(a) of the Lanham Act, 15 U. S. C. §1125(a). Static Control alleged that Lexmark’s misrepresentations had damaged Static Control’s business reputation and impaired its sales.

The Supreme Court was asked to decide what had been styled by the District Court as a “prudential standing issue”: whether Static Control fell within the class of potential Lanham Act plaintiffs. Arguments that Lanham Act plaintiffs may assert standing under the Second Circuit‘s test – requiring a “reasonable interest” and a “reasonable basis” for the plaintiff’s claim of harm – were rejected by the Court.

Instead, in determining the appropriate reach of the Lanham Act, the Court relied on the traditional principles of statutory interpretation. It acknowledged the longstanding principle that the question for courts in determining who was a proper plaintiff was not a matter of judicial “prudence” but rather one of determining the intent of Congress when it authorized certain plaintiffs to sue under §1125(a): “We do not ask whether in our judgment Congress should have authorized Static Control’s suit, but whether Congress in fact did so.”

The Court thus held that, in a statutory cause of action, protection is extended only to those plaintiffs whose interests fall within the zone of interests protected by the law invoked. Because the Lanham Act lists among its purposes the protection of “persons engaged in [interstate commerce] against unfair competition,” and because “unfair competition” is interpreted to be concerned with injuries to business reputation and present and future sales, a lawsuit for false advertising must allege injury to a commercial interest in reputation or sales.

The Court then considered whether the harm alleged in this case was sufficiently similar to the conduct that the Lanham Act prohibits. It held that the harm is required to have been proximately caused by violations of the statute. In the case of a false advertising claim under the Lanham Act, a commercial injury caused by deceiving consumers was held to be a sufficient link between the wrongful act (the false advertising) and the injury (damage to a business’ reputation and/or sales).

The Court concluded that Static Control had adequately pleaded all elements of a Lanham Act cause of action for false advertising.

Practice Tip: The Court held that, in the case of a Lanham Act claim for false advertising, “a direct application of the zone-of-interests test and the proximate-cause requirement supplies the relevant limits on who may sue.” This test excludes as Lanham-Act plaintiffs some who have indisputably been damaged by false advertising. For example, the Lanham Act does not apply to non-business consumers who have been the victims of false advertising, as the Act restricts its class of plaintiffs to those who have suffered an injury to a “commercial interest” in reputation or sales.

Indiana Intellectual Property Law News

Indiana Intellectual Property Law News

Germany and

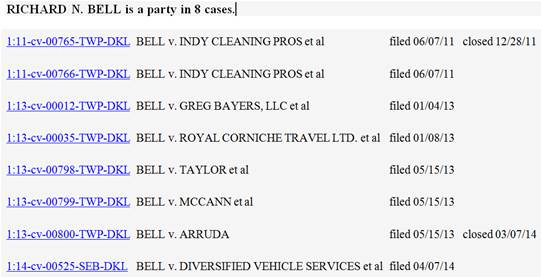

Germany and  Defendants are: Diversified Vehicle Services of Marion County, Indiana; Cameron Taylor and Taylor Computer Solutions of Indianapolis, Indiana; Rhonda Williams of Indianapolis, Indiana; Forensic Solutions, Inc. of Waterford, New York; Heath Garrett of Nashville, Tennessee; CREstacom, Inc. of Fishers, Indiana; American Traveler Service Corp LLC, location unknown;

Defendants are: Diversified Vehicle Services of Marion County, Indiana; Cameron Taylor and Taylor Computer Solutions of Indianapolis, Indiana; Rhonda Williams of Indianapolis, Indiana; Forensic Solutions, Inc. of Waterford, New York; Heath Garrett of Nashville, Tennessee; CREstacom, Inc. of Fishers, Indiana; American Traveler Service Corp LLC, location unknown; individuals infringed trademarks for “ORDER INN”, Registration Nos.

individuals infringed trademarks for “ORDER INN”, Registration Nos.  Indianapolis, Indiana filed a lawsuit in the

Indianapolis, Indiana filed a lawsuit in the  “STRATOTONE” (the “Stratotone mark”),

“STRATOTONE” (the “Stratotone mark”),  Marion Superior Court to deny injunctive relief to

Marion Superior Court to deny injunctive relief to  geographic area restricted.

geographic area restricted. erroneous.

erroneous.  of several

of several  Kresnak and

Kresnak and  Castle, Indiana (“KM”) filed a lawsuit in the

Castle, Indiana (“KM”) filed a lawsuit in the