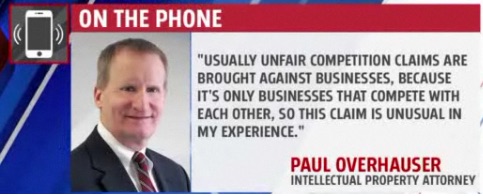

Indianapolis, Indiana – An Indiana trademark attorney for KM Innovations, LLC of New  Castle, Indiana (“KM”) filed a lawsuit in the Southern District of Indiana alleging that Opportunities, Inc. of Colo, Iowa competed unfairly and infringed the trade dress of KM’s “SNOWTIME anytime!” indoor snowballs.

Castle, Indiana (“KM”) filed a lawsuit in the Southern District of Indiana alleging that Opportunities, Inc. of Colo, Iowa competed unfairly and infringed the trade dress of KM’s “SNOWTIME anytime!” indoor snowballs.

The SNOWTIME anytime! concept was conceived in December 2012. At a party, several parents realized that a market might exist for “indoor snowballs,” which would enable children to have a “snowball fight” but without the usual requirements of snow or being outside. KM later introduced a product based on this idea. KM also indicates that it is pursuing a patent on its indoor snowballs.

In this lawsuit for trade dress infringement, which also includes allegations of unfair competition, KM asserts that Opportunities imports, sells and/or is offering to sell polyester-based indoor snowballs and that Opportunities’ indoor snowballs are low-quality knockoffs of KM’s famous product. KM also contends that Opportunities has deliberately copied the distinctive features of KM’s trade dress in an attempt to trade upon the goodwill associated with that trade dress.

To support its contentions of trade dress infringement, KM states that, inter alia, its SNOWTIME anytime! snowballs come in a clear package that includes a label on the front that depicts a mountainous background set in a blue and white theme. At the top of the package, the term “SNOWTIME” appears in a blue that is darker than the lighter blues used elsewhere in the label. The upper part of the lettering is covered with “snow,” giving the commercial impression of fresh snow. Also shown are a blue and white snowball with wording inside and people in snowsuits having fun playing with KM’s indoor-snowball product outdoors.

KM lists several similarities that it contends support a finding of trade dress infringement. It indicates that Opportunities’ packaging includes, among other features: a partially clear exterior that depicts a mountainous background set in a blue and white theme; an illustration of fresh snow covering the words “Snowball Fun” with letters that are a darker blue than the other blues on the package; a generally blue and white snowball with wording inside; and a depiction of people dressed in snowsuits playing outside with the product.

In the complaint, filed by an Indiana trademark lawyer, one count, “Trade Dress Infringement and Unfair Competition” is alleged. KM asks the court for:

• a judgment that Opportunities’ accused packaging infringes KM’s trade dress rights;

• a judgment that Opportunities committed unfair competition by offering its product in the accused packaging;

• damages, including treble damages for willful and deliberate infringement of KM’s trade dress rights and acts of unfair competition;

• a permanent injunction; and

• an award to KM of its attorneys’ fees, costs and expenses.

Practice Tip:

The United States Supreme Court addressed the elements required for trade dress to be protected in Two Pesos, Inc. v. Taco Cabana, Inc., 505 U.S. 763 (1992). In Two Pesos, the Court held that, to establish a cause of action for trade dress infringement, a plaintiff must establish that (a) the design is non-functional; (b) the design is inherently distinctive or distinctive by virtue of having acquired secondary meaning; and (c) there is a likelihood of confusion.

This product was conceived barely a year ago. While SNOWTIME anytime! may have won first place at the Christmas Gift and Hobby Show in Indianapolis, that victory clearly did not take place in November 2012, as was stated in the complaint, as the product did not yet exist.

As a result of the product’s short time in the marketplace, one of the primary hurdles for Plaintiff may be timing. Specifically, if Plaintiff fails to prove that the trade dress in question is inherently distinctive, it could be difficult to prove that secondary meaning has been established in the minds of the consuming public in the time that the product has been available for purchase.

Indiana Intellectual Property Law News

Indiana Intellectual Property Law News

attorneys for

attorneys for

committed trademark infringement of “Tiki Tan”, Trademark Reg. No.

committed trademark infringement of “Tiki Tan”, Trademark Reg. No. Institute’s Project Management Professional (“PMP”) examination and certification process. PMA states that Burch was one of its most-trusted PMP course instructors in the Washington, D.C. area and that, in connection with that position, PMA provided him with access to its proprietary manner of conducting its PMP-examination preparation courses. Moreover, PMA claims that it commissioned Burch and Graywood, Burch’s company, to draft and prepare as a “work for hire” certain training modules that would be for PMA’s exclusive use.

Institute’s Project Management Professional (“PMP”) examination and certification process. PMA states that Burch was one of its most-trusted PMP course instructors in the Washington, D.C. area and that, in connection with that position, PMA provided him with access to its proprietary manner of conducting its PMP-examination preparation courses. Moreover, PMA claims that it commissioned Burch and Graywood, Burch’s company, to draft and prepare as a “work for hire” certain training modules that would be for PMA’s exclusive use.