Indianapolis, Indiana – Pennsylvania trade secret attorneys, in conjunction with Indiana co-counsel, for Distributor Service, Incorporated (“DSI”) of Pennsylvania sued in the Southern District of Indiana alleging that Rusty J. Stevenson (“Stevenson”) of Indiana and Rugby IPD Corp. d/b/a Rugby Architectural Building Products (“Rugby”) of New Hampshire violated an agreement containing non-competition, non-solicitation, and non-disclosure provisions. In the instant order, the court ruled on motions for summary judgment filed by DSI and Stevenson.

Plaintiff DSI is a seller and distributor of wholesale specialty building products to businesses in the Middle Atlantic and Midwest regions of the country. It has eight locations in Indiana, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Kentucky, and Michigan. Defendant Rugby is also in the business of selling and distributing wholesale specialty building products. It does so throughout the United States, including in Indiana, and is a direct competitor of DSI. Stevenson, formerly an employee of DSI, is currently employed by Rugby.

DSI hired Stevenson in October 1999 to be a salesman. When he started, Stevenson had no sales experience in the specialty-building-products industry or any related industry. DSI indicated that it had invested significant time and resources to provide specialized training to Stevenson. In April 2005, DSI promoted Stevenson to the position of sales manager. Later, as part of his employment, Stevenson signed a Confidentiality and Non-Competition Agreement with DSI. This agreement contained provisions for Non-Competition/Non-Solicitation and Non-Disclosure of Confidential Information.

During his employment with DSI, Stevenson had access to information that DSI considered to be protectable as intellectual property assets. This information included all of DSI’s “Customer Lists,” “Customer Product Preferences,” “Competitive Pricing,” and “Competitive Cost Structure” for DSI’s Indianapolis branch. DSI asserted that this information was “the cornerstone of DSI’s ability to compete effectively in the specialty building products industry in Indiana,” and that the information “derives economic value from not being generally known to other persons who can obtain economic value from its disclosure or use.”

In August 2013, Mr. Stevenson resigned from DSI to take a position as the general manager of Rugby’s Indianapolis branch. Shortly thereafter, DSI sued Rugby and Stevenson seeking, inter alia, damages and injunctive relief. DSI asserted claims for: (1) breach of the Non-Compete Provision; (2) breach of the Non-Solicitation Provision; (3) breach of the Non-Disclosure Provision; (4) recovery of attorneys’ fees and expenses under the Agreement; (5) misappropriation of trade secrets; (6) breach of duty of loyalty, and (7) tortious interference.

In this opinion, District Judge Jane Magnus-Stinson reviewed cross-motions for summary judgment filed by DSI and Stevenson. DSI’s motion was denied in its entirety. Stevenson’s motion for summary judgment was granted as to Count 1, breach of the Non-Compete Provision, and Count 2, breach of the Non-Solicitation Provision. Stevenson’s motion for summary judgment on Count 3, breach of the Non-Disclosure Provision, was denied.

The court began by discussing the standard for upholding the provisions at issue. It is a longstanding principle in Indiana that covenants that restrict a person’s employment opportunities are strongly disfavored as a restraint of trade. To be enforceable, such restraints, such as a noncompetition agreement, must be reasonable. The court noted that it, while in many other contexts reasonableness was a question of fact, the reasonableness of a noncompetition agreement was a question of law and, thus, was capable of evaluation in response to the parties’ motions for summary judgment.

The first hurdle for DSI was to show that the agreement protected a legitimate interest, defined as “an advantage possessed by an employer, the use of which by the employee after the end of the employment relationship would make it unfair to allow the employee to compete with the former employer.” Indiana law provides that goodwill, including “secret or confidential information such as the names and addresses of customers and the advantage acquired through representative contact,” is a legitimate protectable interest. DSI argued that it had a legitimate interest in protecting the customer relationships that Stevenson had developed during his years working for DSI as well as the information embodied in DSI’s Customer Lists, Customer Product Preferences, Competitive Pricing, and Competitive Cost Structure, to which Stevenson had been permitted access. The court agreed that this was a protectable interest.

DSI next had to establish that Non-Compete Provision of the agreement was “reasonable in scope as to the time, activity, and geographic area restricted.” DSI argued that the provision was limited merely to restricting Stevenson from engaging in competitive business activity. The court was not convinced. Instead, it noted that, as drafted, the “competitive business activity” restriction applied to the activities of Stevenson’s new employer, not to Stevenson himself. Thus, because Rugby engaged in business activities that were competitive to DSI, the agreement would de facto prohibit Stevenson from working for Rugby in any capacity, despite that no “in-any-capacity” language was explicitly applied to Stevenson in the agreement. “For example,” the court explained, “[under DSI’s agreement,] Mr. Stevenson could not serve lunch in Rugby’s cafeteria or change light bulbs in Rugby’s offices because Rugby competes with DSI.” The court concluded that, as a result, the Non-Compete Provision was overly broad and unreasonable.

Regarding this provision, DSI also contended that alleging and proving that the employee had been provided with trade secrets could render an otherwise unenforceable non-competition clause enforceable. The court rejected this argument.

The court also granted summary judgment for Stevenson on the Non-Solicitation Provision. This provision attempted to restrict Stevenson’s ability to solicit “any customer or prospective customer of [DSI] with which [Stevenson] communicated while employed by [DSI].” The court found this restriction to be vague as to “prospective customer” as well as overbroad and unreasonable in scope.

Finally, the court declined to rule on the Non-Disclosure Provision on summary judgment. It held that, to evaluate whether this provision had been violated, it would need to determine whether “customer lists” and “the identities of key personnel and the requirements of the customers of [DSI]” were confidential. As the evidence submitted regarding confidentiality was “vague, generalized, and conflicting,” the court found that a genuine issue of material fact existed with regard to the Non-Disclosure Provision and, consequently, partial summary judgment in favor of either party was inappropriate on the record before it.

Practice Tip #1: Summary judgment in federal court is guided by Rule 56 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. A motion for summary judgment asks the court to find that a trial on a particular issue or issues is unnecessary because there is no genuine dispute as to any material fact and, instead, the movant is entitled to judgment as a matter of law. The moving party is entitled to summary judgment only if no reasonable fact-finder could return a verdict for the non-moving party.

Practice Tip 2: In a similar case, decided earlier this year, the Indiana Court of Appeals affirmed the trial court’s ruling that the noncompetition agreement binding an ex-employee of the plaintiff was overly broad and, thus, unenforceable.

Continue reading

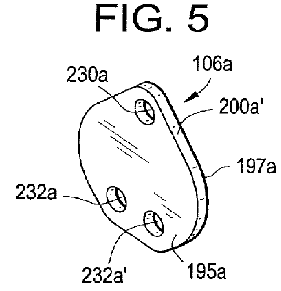

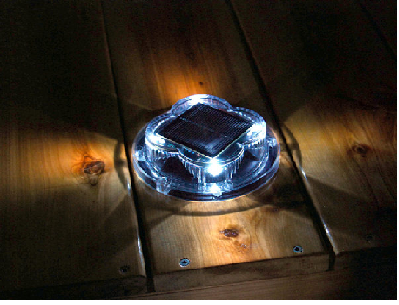

Fort Wayne, Indiana – A patent and copyright attorney for

Fort Wayne, Indiana – A patent and copyright attorney for