Hammond, Indiana – Patent attorneys for Four Mile Bay LLC of Wadsworth, Ohio sued in the Northern District of Indiana alleging that Zimmer Holdings, Inc. of Warsaw, Indiana and Zimmer Dental Inc. of Carlsbad, California infringed DENTAL IMPLANT WITH POROUS BODY, Patent No. 8,684,734, which has been issued by the U.S. Patent Office.

the Northern District of Indiana alleging that Zimmer Holdings, Inc. of Warsaw, Indiana and Zimmer Dental Inc. of Carlsbad, California infringed DENTAL IMPLANT WITH POROUS BODY, Patent No. 8,684,734, which has been issued by the U.S. Patent Office.

Defendant Zimmer Holdings designs, develops, manufactures, and markets reconstructive orthopedic implants, including dental implants. Defendant Zimmer Dental, a division of Zimmer Holdings, is engaged in a similar business. The two Zimmer entities have been sued by Four Mile Bay for patent infringement.

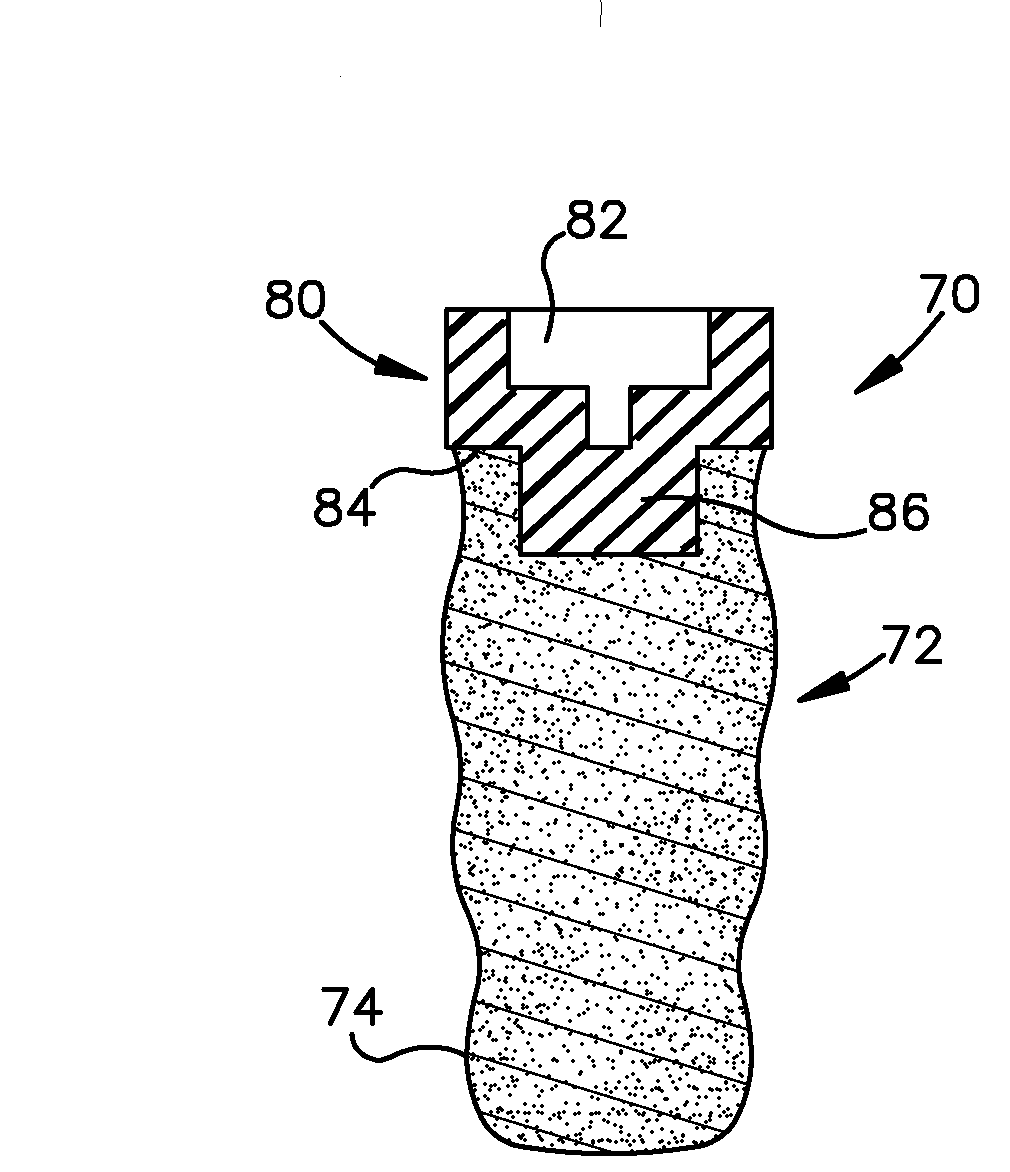

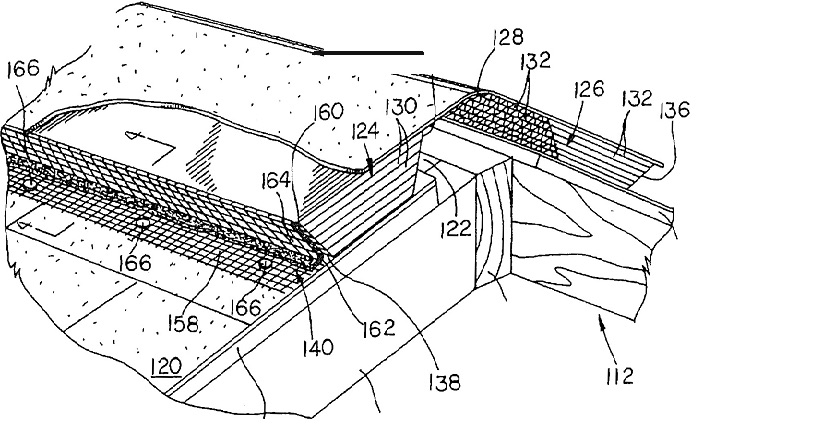

The subject of the dispute is Patent No. 8,684,734 (the “‘734 patent”), which relates to the “osseointegration” of dental implants into a patient. A dental implant designed for osseointegration provides porous structures to which a patient’s bone may grow an attachment. Four Mile Bay indicates that prior art in the area was limited to providing a surface-level solution, wherein bone surrounding the implant could grow into the coating only on the outside of the implant.

Four Mile Bay contends that the ‘734 patent addresses this shortcoming of the prior technology by including porous structures to which bone can adhere that extend through a “significant part” of the implant. This, it states, allows the patient’s bone to grow completely through the implant and provides improved anchoring within the mouth. The invention also includes an internal cavity that may house a substance that stimulates bone growth.

Four Mile Bay contends in this current patent infringement litigation that Zimmer Holdings and Zimmer Dental are infringing the ‘734 patent. In the complaint, filed by Illinois patent attorneys for Four Mile Bay, the following are claims are asserted:

• Count I: Patent Infringement Against Zimmer Holdings

• Count II: Patent Infringement Against Zimmer Dental

Four Mile Bay asks the court for a judgment that defendants have directly infringed claims of the ‘734 patent, for a reasonable royalty and for pre- and post-judgment interest.

Practice Tip:

The concept of “prior art” appears simple upon first glance. It might be briefly defined as “all information that was publically available before a relevant date [often 12 months prior to a U.S. patent application being filed] that could be pertinent to a patent’s claim of originality.”

However, the legal nuances of what is “new” and what constitutes “prior art,” along with the difficulties in performing an adequate worldwide search of printed materials for references to claims in a pending application, makes performing a complete patentability assessment a daunting prospect for even the most experienced inventor. Thus, while an inventor is wise to conduct his or her own patent search initially, it is important to hire an experienced patent attorney to perform a thorough patent search and assessment of patentability.

New York (“BMI”),

New York (“BMI”),  Germany and

Germany and  York (“CleanTech”), filed a patent infringement lawsuit in the

York (“CleanTech”), filed a patent infringement lawsuit in the  filed a lawsuit in the

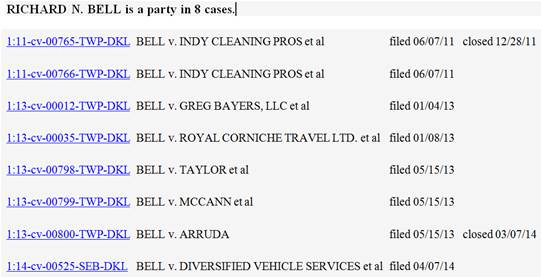

filed a lawsuit in the  Defendants are: Diversified Vehicle Services of Marion County, Indiana; Cameron Taylor and Taylor Computer Solutions of Indianapolis, Indiana; Rhonda Williams of Indianapolis, Indiana; Forensic Solutions, Inc. of Waterford, New York; Heath Garrett of Nashville, Tennessee; CREstacom, Inc. of Fishers, Indiana; American Traveler Service Corp LLC, location unknown;

Defendants are: Diversified Vehicle Services of Marion County, Indiana; Cameron Taylor and Taylor Computer Solutions of Indianapolis, Indiana; Rhonda Williams of Indianapolis, Indiana; Forensic Solutions, Inc. of Waterford, New York; Heath Garrett of Nashville, Tennessee; CREstacom, Inc. of Fishers, Indiana; American Traveler Service Corp LLC, location unknown; “IP Jurisprudence in the New Technological Epoch: The Judiciary’s Role in the Age of Biotechnology and Digital Media.” The program will run from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. and will provide 6.5 hours of continuing legal education.

“IP Jurisprudence in the New Technological Epoch: The Judiciary’s Role in the Age of Biotechnology and Digital Media.” The program will run from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. and will provide 6.5 hours of continuing legal education. individuals infringed trademarks for “ORDER INN”, Registration Nos.

individuals infringed trademarks for “ORDER INN”, Registration Nos.  Indianapolis, Indiana filed a lawsuit in the

Indianapolis, Indiana filed a lawsuit in the