Indianapolis, Indiana – Cummins Inc. of Columbus, Indiana has sued in the Southern District of Indiana alleging counterfeiting, trademark infringement and trademark dilution by T’Shirt Factory of Greenwood, Indiana; Freedom Custom Z of Bloomington, Indiana; Shamir Harutyunyan of Panama City Beach, Florida and Doe Defendants 1 – 10. Defendants are accused of infringing various trademarks, including those protected by Trademark Registration Nos. 4,103,161 and 1,090,272, which have been registered by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

Cummins was founded nearly a century ago and is a global power leader with complementary business units that design, manufacture, distribute and service engines and related  technologies, including fuel systems, controls, air handling, filtration, emission solutions and electrical power generation systems. Cummins employs approximately 46,000 people worldwide and serves customers in approximately 190 countries.

technologies, including fuel systems, controls, air handling, filtration, emission solutions and electrical power generation systems. Cummins employs approximately 46,000 people worldwide and serves customers in approximately 190 countries.

Defendants include T’Shirt Factory and Shamir Harutyunyan, who is alleged to be an owner, agent, and/or officer of T’Shirt Factory. Cummins claims that Harutyunyan was personally aware of, and authorized and/or participated in, the wrongful conduct alleged in Cummins’ complaint. Freedom Custom Z is also named as a Defendant. Its business purportedly includes the sale of t-shirts, sweatshirts and other apparel upon which logos have been printed or affixed. Doe Defendants 1 – 10, the identities of whom are currently unknown, have also been accused of the illegal acts alleged.

Cummins states that it owns and maintains hundreds of trademark registrations worldwide covering a broad spectrum of goods and services. Among those is Trademark Registration No. 4,126,680, which covers the following goods: “Men’s and women’s clothing, namely, sweatshirts, hooded sweatshirts, aprons, shirts, sport shirts, jackets, t-shirts, polo shirts, baseball caps and hats, ski caps, fleece caps, headbands, scarves, quilted vests, coveralls, leather jackets, t-shirts for toddlers and children” in International Class 25.

Cummins also asserts that it owns Trademark Registration No. 4,103,161. It indicates that this trademark registration covers the following goods: “Men’s and women’s clothing, namely, sweatshirts, hooded sweatshirts, aprons, shirts, sport shirts, jackets, t-shirts, polo shirts, baseball caps and hats, ski caps, fleece caps, headbands, scarves, quilted vests, coveralls, leather jackets, t-shirts for toddlers and children” in International Class 25. Cummins also states that it owns Trademark Registration No. 4,305,797, registered for similar goods.

Finally, Cummins claims Trademark Registration Nos. 579,346; 1,090,272 and 1,124,765, which also relate to the Cummins Mark, as its intellectual property.

In December 2013, Cummins employees observed apparel bearing the Cummins Marks offered for sale at kiosks located in the College Mall in Bloomington, Indiana; in the Greenwood Park Mall in Greenwood, Indiana; and in the Castleton Mall in Indianapolis, Indiana.

Trademark lawyers for Cummins have sued in the Southern District of Indiana. Cummins accuses Defendants of having acted intentionally, willfully and maliciously. It makes the following claims in its complaint:

• Count I: Trademark Infringement Under Section 43(a) of the Lanham Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1125(a)

• Count II: Trademark Dilution Under Section 43(c) of the Lanham Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1125(c)

• Count III: Trademark Counterfeiting Under Section 32(1) of the Lanham Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1114(1)

Cummins asks 1) for a temporary restraining order allowing inspection and seizure of the accused goods as well as enjoining Defendants from, inter alia, manufacturing or selling items bearing counterfeit Cummins Marks; 2) for preliminary and permanent injunctions prohibiting Defendants from, inter alia, manufacturing or selling items bearing counterfeit Cummins Marks; and 3) that the court order the destruction of all unauthorized goods.

It also asks the court to find that the Defendants 1) have infringed Cummins’ trademarks in violation of 15 U.S.C. § 1114; 2) have created a false designation of origin and false representation of association in violation of 15 U.S.C. § 1125(a); 3) have diluted Cummins’ famous trademarks in violation of 15 U.S.C. § 1125(c) and 4) have willfully infringed.

Cummins asks for Defendants’ profits from the sales of the infringing and counterfeit goods bearing the Cummins Marks; treble actual damages, costs, reasonable attorneys’ fees as well as pre-judgment and post-judgment interest.

Practice Tip: Repercussions for counterfeiting are not limited to the damages that can be awarded for civil wrongdoing. Increasingly, defendants who engage in counterfeiting, especially counterfeiting on a large scale or during high-profile events, can find themselves facing criminal charges (see, e.g., an arrest made on allegations of counterfeiting during Super Bowl XLVI) in addition to being sued by the owner of the trademark.

Continue reading

economic treaty, encompassing nations representing more than 40 percent of the world’s gross domestic product (“GDP”). The WikiLeaks release of the text came ahead of the decisive TPP Chief Negotiators summit in Salt Lake City, Utah. The chapter published by WikiLeaks is perhaps the most controversial chapter of the TPP due to its wide-ranging effects on medicines, publishers, internet services, civil liberties and biological patents. Significantly, the released text includes the negotiation positions and disagreements between all 12 prospective member states.

economic treaty, encompassing nations representing more than 40 percent of the world’s gross domestic product (“GDP”). The WikiLeaks release of the text came ahead of the decisive TPP Chief Negotiators summit in Salt Lake City, Utah. The chapter published by WikiLeaks is perhaps the most controversial chapter of the TPP due to its wide-ranging effects on medicines, publishers, internet services, civil liberties and biological patents. Significantly, the released text includes the negotiation positions and disagreements between all 12 prospective member states.

predecessor, the Continental Air Defense Command, have tracked Santa’s flight around the world. Their high-technology approach includes not only radar and satellites in geo-synchronous orbit but also the recent additions of strategically placed SantaCams and jet pilots flying F-15s, F-16s and F-22s to escort Santa as he delivers presents to children on the “nice” list worldwide.

predecessor, the Continental Air Defense Command, have tracked Santa’s flight around the world. Their high-technology approach includes not only radar and satellites in geo-synchronous orbit but also the recent additions of strategically placed SantaCams and jet pilots flying F-15s, F-16s and F-22s to escort Santa as he delivers presents to children on the “nice” list worldwide.  CleanTech sued

CleanTech sued IURTC is a not-for-profit corporation that fosters collaboration between

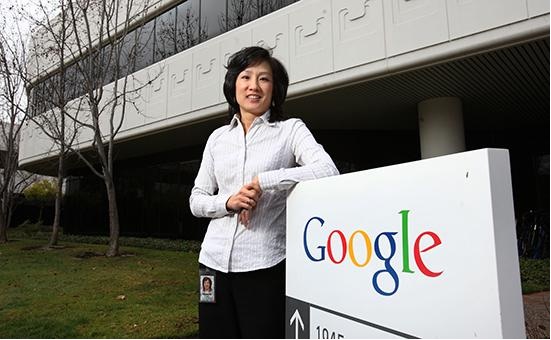

IURTC is a not-for-profit corporation that fosters collaboration between  While Director of the USPTO’s Silicon Valley satellite office, Lee has served as the agency’s primary liaison with the innovation community in the Silicon Valley and West Coast, leading the establishment of a temporary office in Menlo Park and working creatively with California’s Congressional, state, and local leadership to successfully secure a permanent office location in San Jose. In that role, she has also been actively engaged in education and outreach initiatives, empowering the USPTO to more effectively develop programs, policies, and procedures to meet the needs of the West Coast innovation community. Beyond the Silicon Valley office, Lee has also played a broader role in helping shape key policy matters impacting the nation’s intellectual property (IP) system, focusing closely on efforts to continually strengthen patent quality, as well as curbing abusive patent litigation. Prior to becoming Director of the Silicon Valley USPTO, Lee served two terms on the USPTO’s Patent Public Advisory Committee, whose members are appointed by the U.S. Commerce Secretary and serve to advise the USPTO on its policies, goals, performance, budget and user fees.

While Director of the USPTO’s Silicon Valley satellite office, Lee has served as the agency’s primary liaison with the innovation community in the Silicon Valley and West Coast, leading the establishment of a temporary office in Menlo Park and working creatively with California’s Congressional, state, and local leadership to successfully secure a permanent office location in San Jose. In that role, she has also been actively engaged in education and outreach initiatives, empowering the USPTO to more effectively develop programs, policies, and procedures to meet the needs of the West Coast innovation community. Beyond the Silicon Valley office, Lee has also played a broader role in helping shape key policy matters impacting the nation’s intellectual property (IP) system, focusing closely on efforts to continually strengthen patent quality, as well as curbing abusive patent litigation. Prior to becoming Director of the Silicon Valley USPTO, Lee served two terms on the USPTO’s Patent Public Advisory Committee, whose members are appointed by the U.S. Commerce Secretary and serve to advise the USPTO on its policies, goals, performance, budget and user fees. J & J Sports states that it is the exclusive domestic commercial distributor of the Program. It has sued Geo-Joe, as well as Christine Kotsopoulos as an individual, under the Communications Act of 1934 and The Cable & Television Consumer Protection and Competition Act of 1992.

J & J Sports states that it is the exclusive domestic commercial distributor of the Program. It has sued Geo-Joe, as well as Christine Kotsopoulos as an individual, under the Communications Act of 1934 and The Cable & Television Consumer Protection and Competition Act of 1992. technologies, including fuel systems, controls, air handling, filtration, emission solutions and electrical power generation systems. Cummins employs approximately 46,000 people worldwide and serves customers in approximately 190 countries.

technologies, including fuel systems, controls, air handling, filtration, emission solutions and electrical power generation systems. Cummins employs approximately 46,000 people worldwide and serves customers in approximately 190 countries. . applicants will be able to file a single application for protection of an industrial design which will have effect in more than 40 territories.

. applicants will be able to file a single application for protection of an industrial design which will have effect in more than 40 territories. Redwall is a consulting and design services firm engaged in the business of strategic branding and advertising. Its services include, but are not limited to, developing a clear message and a unique visual image as well as developing brand value for its clients.

Redwall is a consulting and design services firm engaged in the business of strategic branding and advertising. Its services include, but are not limited to, developing a clear message and a unique visual image as well as developing brand value for its clients. Redwall asserts that, despite its performance in full, ESG has failed to pay to Redwall the remaining balance for the work completed. It also claims that ESG has used and continues to use Redwall’s copyrighted Design on a variety of items including, but not limited to, its website and traffic barricades.

Redwall asserts that, despite its performance in full, ESG has failed to pay to Redwall the remaining balance for the work completed. It also claims that ESG has used and continues to use Redwall’s copyrighted Design on a variety of items including, but not limited to, its website and traffic barricades.