Coach Sues Downtown Gift Shop and Chun Ying Huang for Trademark Infringement, Forgery and Counterfeiting – 1

South Bend, Ind. — Trademark lawyers for Coach, Inc. of New York, N.Y. and Coach Services, Inc. of Jacksonville, Fla. (collectively, “Coach”) sued Downtown Gift Shop of Mishawaka, Ind. and Chun Ying Huang of Granger, Ind. (“Huang”) alleging various violations of intellectual-property law, including trademark infringement, forgery and counterfeiting.

Coach was founded more than 70 years ago as a family-run workshop in Manhattan. Since then, the company has been engaged in the manufacture, marketing and sale of fine leather and mixed-material products including handbags, wallets and accessories including eyewear, footwear, jewelry and watches. Coach products have also become among the most popular in the world, with Coach’s annual global sales currently exceeding three billion dollars.

Coach was founded more than 70 years ago as a family-run workshop in Manhattan. Since then, the company has been engaged in the manufacture, marketing and sale of fine leather and mixed-material products including handbags, wallets and accessories including eyewear, footwear, jewelry and watches. Coach products have also become among the most popular in the world, with Coach’s annual global sales currently exceeding three billion dollars.

On December 8, 2012, a private investigator from Coach visited the Downtown Gift Shop and observed thousands of handbags, boots, and accessories displayed for sale. These items bore the trademarks of many high-end brands including Coach, Louis Vuitton, Chanel and Tiffany.

On December 11, 2012, investigators from Coach accompanied officers from the St. Joseph County Police Department, Indiana State Police Department, and the Department of Homeland Security, to execute a search warrant on Downtown Gift Shop.

The investigators and officers identified, photographed, and seized over 3,000 counterfeit trademarked merchandize, including over 1,000 Coach handbags, wallets, scarves, sunglasses, jewelry, and hats. Coach contends that all of the seized items are counterfeit.

Coach, the owner of at least 47 trademarks, subsequently sued Downtown Gift Shop and Huang, whom Coach contends is individually liable for any infringing activities. It alleges that Downtown Gift Shop and Huang are engaged in designing, manufacturing, advertising, promoting, distributing, selling, and/or offering for sale products bearing logos and source-identifying indicia and design elements that are studied imitations of the Coach trademarks.

The complaint includes counts for trademark infringement, false designation of origin and false advertising under the Lanham Act, 15 U.S.C. §§ 1114, 1116, 1117, 1125(a) and (c); trademark infringement and unfair competition under the common law of the State of Indiana; and forgery under Indiana Code § 35- 43-5-2(b) as well as counterfeiting under Indiana Code § 35-43-5-2(a), pursuant to Indiana Code § 34-24-3-1. These counts are listed as:

· COUNT I (Trademark Counterfeiting, 15 U.S.C. § 1114)

· COUNT II (Trademark Infringement, 15 U.S.C. § 1114)

· COUNT III (False Designation of Origin and False Advertising, 15 U.S.C. § 1125(a))

· COUNT IV (Common Law Trademark Infringement)

· COUNT VII [sic] (Common Law Unfair Competition)

· COUNT VIII (Forgery Under Ind. Code § 35-43-5-2(b))

· COUNT IX (Counterfeiting Under Ind. Code § 35-43-5-2(a))

· COUNT X (Common Law Unjust Enrichment)

· COUNT XI (Attorneys’ Fees)

Coach asks the court, inter alia, to enter judgment against the defendants on all counts; for an injunction against further wrongful activity; to order that all infringing materials be recalled and disposed of; to award to Coach statutory damages of $2,000,000 per counterfeit mark per type of good; to award punitive damages; and to award to Coach its costs and attorneys’ fees.

Practice Tip: Homeland Security Investigations (“HSI”), a directorate of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, is one of the agencies charged with investigating counterfeit goods. Much of the sales volume of counterfeit goods has moved to the Internet and, as part of its efforts, HSI is authorized to petition a court to order the seizure of domain names of websites selling counterfeit goods over the Internet.

One such seized domain name, http://designsfauxreal.com/, has been redesigned by HSI as a warning for visitors and includes such advertising copy as “FREE identity theft with every purchase” and “LOOK! Low quality counterfeit product. On closer inspection, alligator may resemble a tadpole.”

J & J Sports Sues Juan Aguirre and Mi Pueblo V Mexican Restaurant for Unauthorized Interception and Broadcast of Championship Fight

South Bend, Ind. — Intellectual property lawyers for J & J Sports Productions, Inc. of Campbell, Calif. sued Juan M. Aguirre (“Aguirre”) and Mi Pueblo V Mexican Restaurant of Wabash, Ind. (“Mi Pueblo”) alleging the illegal interception and display of a pay-per-view championship fight.

J &  J Sports, the exclusive domestic commercial distributor of Ultimate Fighting Championship 131: Junior Dos Santos v. Shane Carwin, (the “program”) has sued Mi Pueblo and Aguirre, an officer of the restaurant, under the Communications Act of 1934 and The Cable & Television Consumer Protection and Competition Act of 1992.

J Sports, the exclusive domestic commercial distributor of Ultimate Fighting Championship 131: Junior Dos Santos v. Shane Carwin, (the “program”) has sued Mi Pueblo and Aguirre, an officer of the restaurant, under the Communications Act of 1934 and The Cable & Television Consumer Protection and Competition Act of 1992.

The defendants have been accused of violating 47 U.S.C. § 605 and 47 U.S.C. § 553 by displaying the program on June 11, 2011 without a commercial license. Regarding the claim under 47 U.S.C. § 605, the complaint alleges that with “full knowledge that the Program was not to be intercepted, received, published, divulged, displayed, and/or exhibited by commercial entities unauthorized to do so, each and every one of the above named Defendants . . . did unlawfully intercept, receive, publish, divulge, display, and/or exhibit the Program” for the purpose of commercial advantage and/or private financial gain. The allegation of interception under 47 U.S.C. § 605 is a different cause of action from copyright infringement. That claim has a two-year statute of limitations, which explains why the complaints were filed on June 11, 2013.

A count of conversion is also included which asserts that the acts of the Mi Pueblo and Aguirre were “willful, malicious, egregious, and intentionally designed to harm Plaintiff J & J Sports” and that, as a result of being deprived of their commercial license fee, J & J Sports suffered “severe economic distress and great financial loss.”

The complaint seeks statutory damages of $100,000 for each violation of 47 U.S.C. § 605; $10,000 for each violation of 47 U.S.C. § 553; $50,000 for each willful violation of 47 U.S.C. § 553; costs and attorney fees.

Practice Tip #1: The body of the complaint listed a second individual defendant, Loida Chavarria, in paragraph 10 but she was not listed in the caption as a party. The reason for this disparity was unclear from reading the complaint itself. However, a review of another recent complaint filed by this attorney on behalf of J & J Sports (see here), in which J & J Sports sued an Indianapolis night club with nearly identical allegations, reveals that Ms. Chavarria was listed there, in paragraph 10, as a defendant. It appears that J & J Sports, which filed 708 lawsuits in 2011, neglected to remove her from a complaint template that had previously been filled in with a different set of defendants.

Practice Tip #2: This lawsuit was filed on the two-year anniversary of the program that the defendants are alleged to have illegally broadcast. When Congress passed the Cable Communication Act, a statute of limitations was not included. Some federal courts have determined that a two-year statute of limitation is appropriate while other federal courts have used a three-year statute of limitations.

We have blogged before about J & J Sports here, here and here.

Overhauser Law Offices, the publisher of this website, has represented several hundred persons and businesses accused of infringing satellite signals.

This case has been assigned to The Honorable Judge Rudy Lozano and Magistrate Judge Christopher A. Nuechterlein, and assigned Case No. 3:13-cv-00571-RL-CAN. Continue reading

Microsoft Sues Mister HardDrive and Mark Cady for Copyright and Trademark Infringement

New Albany, Ind. — Intellectual property lawyers for Microsoft Corp. of Redmond, Wash. sued  Mister HardDrive and Mark Cady of Scottsburg, Ind. alleging infringement of copyrighted work TX 5-407-055 titled Microsoft Windows XP Professional : version 2002 registered with the U.S. Copyright Office; and Trademark Registration Nos. 1,200,236; 1,256,083; 1,872,264 and 2,744,843 registered with the U.S. Trademark Office.

Mister HardDrive and Mark Cady of Scottsburg, Ind. alleging infringement of copyrighted work TX 5-407-055 titled Microsoft Windows XP Professional : version 2002 registered with the U.S. Copyright Office; and Trademark Registration Nos. 1,200,236; 1,256,083; 1,872,264 and 2,744,843 registered with the U.S. Trademark Office.

Microsoft, the seventh largest publically traded company in the world, has sued Mister Harddrive, a business entity of unknown legal structure that is also known as Mister HardDrive’s Wipe and Restore (“Mister HardDrive”), and Mark Cady, an individual, alleging that they engaged in copyright and trademark infringement; false designation of origin, false description and representation; and unfair competition.

Microsoft develops, markets, distributes and licenses computer software. Microsoft’s software programs are recorded on discs, and they are packaged and distributed together with associated proprietary materials such as user’s guides, user’s manuals, end user license agreements, and other components. Mister HardDrive is engaged in the business of advertising, marketing, installing, offering, and distributing computer hardware and software, including products sold as Microsoft software.

In its complaint, Microsoft alleges that Mister HardDrive and Mark Cady offered, installed, and distributed unauthorized copies of Microsoft software and thereby infringed Microsoft’s copyrights, trademarks and/or service mark. Infringement and/or misappropriation of Microsoft’s copyrights, advertising ideas, style of doing business, slogans, trademarks and/or service mark in defendants’ advertising is also alleged.

Microsoft asserts that in December 2012, defendants were found to have distributed computer systems with unauthorized copies of Windows XP installed on them. Microsoft asked defendants to stop making and distributing infringing copies of Microsoft software but claims that additional computers with unauthorized copies of Windows XP were subsequently distributed by defendants. Microsoft claims that such distribution of counterfeit and infringing copies of their software — along with related infringing items — is ongoing.

The complaint lists the following counts:

· First Claim [Copyright Infringement – 17 U.S.C. § 501, et seq.]

· Second Claim [Trademark Infringement – 15 U.S.C. § 1114]

· Third Claim [False Designation Of Origin, False Description And Representation –

· 15 U.S.C. § 1125 et seq.]

· Fourth Claim [Indiana Common Law Unfair Competition]

· Fifth Claim [For Imposition Of A Constructive Trust Upon Illegal Profits]

· Sixth Claim [Accounting]

Microsoft asks that the court adjudge that the defendants have willfully infringed its federally registered copyright; that the defendants have willfully infringed several of its federally registered trademarks and one of its service marks; that the defendants have committed and are committing acts of false designation of origin, false or misleading description of fact, and false or misleading representation against Microsoft; and that the defendants have engaged in unfair competition in violation of Indiana common law.

Microsoft seeks damages, an accounting, the imposition of a constructive trust upon defendants’ illegal profits, and injunctive relief.

Practice Tip: Microsoft has named as defendants both the business entity and the individual who has been identified as related to Mister HardDrive as “an owner, operator, officer, [or] shareholder, [who] does business as and/or otherwise controls” the business. A corporate officer, director or shareholder is, as a general matter, personally liable for all torts which he authorizes or directs or in which he participates, even if he acted as an agent of the corporation and not on his own behalf.

Australian Gold Sues Devoted Creations for Trademark Infringement of LIVE LAUGH TAN®

Indianapolis, Ind. — Trademark lawyers for Australian Gold, LLC of Indianapolis, Ind. sued in  the Southern District of Indiana alleging that Devoted Creations, Inc. of Oldsmar, Fla. intentionally and willfully infringed its trademark, Registration No. 4,154,194, for “LIVE LAUGH TAN,” which is registered with the U.S. Trademark Office.

the Southern District of Indiana alleging that Devoted Creations, Inc. of Oldsmar, Fla. intentionally and willfully infringed its trademark, Registration No. 4,154,194, for “LIVE LAUGH TAN,” which is registered with the U.S. Trademark Office.

Australian Gold has been in the business of selling indoor-tanning preparations for over 20 years. Devoted Creations also sells indoor-tanning preparations and is a competitor of Australian Gold. Australian Gold contends that, since at least October 2010, it has used the registered mark “LIVE LAUGH TAN” as a trade name and trademark in conjunction with sales of its Australian Gold line of indoor-tanning products. Australian Gold asserts that it has used the LIVE LAUGH TAN mark continuously, notoriously and extensively with respect to sales of the preparations since that time. It claims that, as a result of its promotional activities, the mark has acquired substantial goodwill. It also states that the mark is both “distinctive” and “inherently distinctive” and that it serves to distinguish Australian Gold’s indoor-tanning preparations from those of others.

Devoted Creations advertises its indoor-tanning preparations under the name “LIVE LOVE TAN.” Australian Gold asserts that Devoted Creations is aware that Australian Gold’s customers use the LIVE LAUGH TAN mark to identify Australian Gold products and that the designation LIVE LOVE TAN was an intentional and willful copy. It claims that Devoted Creations acted in bad faith and with full knowledge and conscious disregard of Australian Gold’s rights and that, as a result, this is an exceptional case. It further states that Devoted Creations’ mark is substantially identical, that its indoor-tanning products directly compete with those of Australian Gold and that those products are for sale in the same channels of trade. Finally, Australian Gold claims that Devoted Creations derives significant revenue from products sold using LIVE LOVE TAN and that such use of the mark is likely to cause confusion among consumers regarding the origins of Devoted Creations’ goods and to diminish goodwill associated with Australian Gold’s LIVE LAUGH TAN mark.

Devoted Creations advertises its indoor-tanning preparations under the name “LIVE LOVE TAN.” Australian Gold asserts that Devoted Creations is aware that Australian Gold’s customers use the LIVE LAUGH TAN mark to identify Australian Gold products and that the designation LIVE LOVE TAN was an intentional and willful copy. It claims that Devoted Creations acted in bad faith and with full knowledge and conscious disregard of Australian Gold’s rights and that, as a result, this is an exceptional case. It further states that Devoted Creations’ mark is substantially identical, that its indoor-tanning products directly compete with those of Australian Gold and that those products are for sale in the same channels of trade. Finally, Australian Gold claims that Devoted Creations derives significant revenue from products sold using LIVE LOVE TAN and that such use of the mark is likely to cause confusion among consumers regarding the origins of Devoted Creations’ goods and to diminish goodwill associated with Australian Gold’s LIVE LAUGH TAN mark.

Australian Gold’s complaint lists a count of “Federal and Common Law Trademark Infringement” and a count of “Unfair Competition.” It seeks a judgment that the use of LIVE LOVE TAN infringes its mark; an injunction against confusing advertising or sales by Devoted Creations; damages, costs and attorney’s fees; and an award of any wrongful profits made by Devoted Creations.

Practice Tip: Australian Gold’s decision to trademark LIVE LAUGH TAN as a mark for “Tote bags” is a curious one, as tote bags are not the products at issue. While the United States Patent and Trademark Office will not provide legal advice online concerning an individual’s particular circumstance, in addressing similar situations, it states, “similar trademark registrations can co-exist on the register so long as the goods or services identified in the registration are adequately different so as not to raise a likelihood of confusion in the purchasing public.”

Leon Isaac Kennedy Sues GoDaddy, Spirit Media, Arthur Phoenix and Five Doe Defendants for Purchase of Leonisaackennedy.com

Indianapolis, Ind. – A trademark lawyer for American actor, minister, producer and writer Leon Isaac Kennedy of Burbank, Calif. sued alleging Lanham Act violations, unfair competition and violations of various Indiana state statutes as a result of defendants’ purchase of the domain name Leonisaackennedy.com. The defendants are GoDaddy.com, LLC of Scottsdale, Ariz., Spirit Media of Phoenix, Ariz., Arthur Phoenix of Phoenix, Ariz. and John Does 1-5.

violations of various Indiana state statutes as a result of defendants’ purchase of the domain name Leonisaackennedy.com. The defendants are GoDaddy.com, LLC of Scottsdale, Ariz., Spirit Media of Phoenix, Ariz., Arthur Phoenix of Phoenix, Ariz. and John Does 1-5.

In a complaint for damages and injunctive relief, Kennedy alleges that the defendants have violated his intellectual p roperty rights by purchasing a domain name consisting of Kennedy’s first, middle and last name. Spirit Media is the registrant and owner of the domain name. Phoenix is also listed as a registrant. GoDaddy is the current registrar.

roperty rights by purchasing a domain name consisting of Kennedy’s first, middle and last name. Spirit Media is the registrant and owner of the domain name. Phoenix is also listed as a registrant. GoDaddy is the current registrar.

Kennedy claims that no content has ever been placed on the domain website and that the defendants have offered the domain name for sale for $5,000 at a domain auction. He asserts that this “use of the Domain violates the “Anti Cybersquatting Piracy [sic] Act.”

Kennedy asserts ownership of all interests in his name, image, likeness and voice (“Kennedy right of publicity”) as well as other intellectual property rights such as trademarks, copyrights and rights of association as associated with the Kennedy right of publicity. He alleges that  the purchase constitutes unauthorized and illegal commercial use and registration of a domain name and violates his personal and/or property rights. He further claims that this commercial use has siphoned the goodwill from his various property interests and asserts that he has been irreparably harmed as a result.

the purchase constitutes unauthorized and illegal commercial use and registration of a domain name and violates his personal and/or property rights. He further claims that this commercial use has siphoned the goodwill from his various property interests and asserts that he has been irreparably harmed as a result.

The complaint lists seven claims:

· Count I: Violation of Section 1125 (a) of the Lanham Act

· Count II: Violation of Section 1125 (d) of the Lanham Act

· Count III: Unfair Competition

· Count IV: Violation of Indiana Right of Publicity

· Count V: Conversion (I.C. § 35-43-4-3)

· Count VI: Deception I.C. § 35-43-5-3(a)(6)

· Count VII: Indiana Crime Victims’ Act I.C. § 35-24-3-1

Kennedy asks for the immediate transfer of the domain name to him; an injunction enjoining the defendants from future use of Kennedy’s intellectual property; an order directing the immediate surrender of any materials featuring Kennedy’s intellectual property; damages, including treble damages; costs and attorneys’ fees.

This complaint, initially filed in an Indiana state court, was removed by GoDaddy to federal court.

Practice Tip #1: The Anticybersquatting Consumer Protection Act was enacted to create a cause of action for registering, trafficking in or using a domain name confusingly similar to, or dilutive of, a trademark or personal name. Despite alleging malicious behavior on the part of all defendants, including GoDaddy, it will be tricky to pursue this count against GoDaddy, a domain-name registrar. Under § 1125(d)(2)(D)(ii), the “domain name registrar or registry or other domain name authority shall not be liable for injunctive or monetary relief under this paragraph except in the case of bad faith or reckless disregard, which includes a willful failure to comply with any such court order.”

Practice Tip #2: I.C. §§ 35-43-4-3 and 35-43-5-3(a)(6) are criminal statutes, claimed in the complaint in conjunction with an attempt to parlay the accusation into an award for damages, costs and attorneys’ fees. The Indiana Court of Appeals has discussed “theft” and “conversion” as they pertain to takings of intellectual property in several recent cases (see, for example, here and here) and has made it clear that criminal statutes often apply differently to an unlawful taking of intellectual property.

Practice Tip #3: This complaint was submitted by Theodore Minch, who is, coincidentally, also the attorney for LeeWay Media, about which we blogged yesterday. As with LeeWay, none of the parties seems to have much connection to Indiana. It will be interesting as the case develops to analyze the rationale behind the decision to file in an Indiana court.

Continue reading

Bruce Lee’s Daughter Sues Regarding 1965 Bruce Lee Screen Test

Indianapolis, Ind. — Copyright lawyers for LeeWay Media Group, LLC of Los Angeles, Calif. filed a declaratory judgment suit against Laurence Joachim of New York, N.Y. and Los Angeles, Calif. and Trans-National Film Corporation of New York in a copyright dispute over  the use of portions of Bruce Lee’s 1965 screen test in the 2012 documentary “I Am Bruce Lee.”

the use of portions of Bruce Lee’s 1965 screen test in the 2012 documentary “I Am Bruce Lee.”

Bruce Lee, widely considered to have been one of the most influential martial artists of all time, was also an actor and filmmaker. He is most famous for his roles in the films The Big Boss (1971), Fist of Fury (1972), Way of the Dragon (1972), Enter the Dragon (1973) and The Game of Death (1978). Lee was the first celebrity to be cast in major motion pictures after his death.

Lee completed his first Hollywood screen test in or about 1965. It is over eight minutes long and, according to LeeWay Media, has been used freely in many productions over the intervening decades. It is allegedly available for viewing on such sites as youtube.com.

A documentary about Lee entitled I Am Bruce Lee was produced by LeeWay Media, a company founded by Lee’s daughter Shannon Lee. It was released and aired on Spike TV in early 2012. Approximately 91 seconds of the 1965 screen test were included in the documentary. Prior to including the material from the screen test, LeeWay Media searched to determine whether the screen test was copyrighted. It concluded that the material was in the public domain.

LeeWay Media was contacted in July 2012 by Joachim, who claimed to own the copyright to the screen-test footage. He asserted that his copyright had been infringed. Negotiations ensued, but the dispute was not resolved. Among other issues, LeeWay Media asserted that it had requested but not received any relevant copyright-ownership documentation from Joachim.

In May 2013, Joachim informed LeeWay Media that, unless a six-figure settlement fee was paid, he would sue for violations of federal copyright law; federal law for unfair competition; and Indiana and California state law for unfair competition. LeeWay Media instead filed suit against Joachim and Trans-National Film under the Declaratory Judgment Act, asking the court to declare, inter alia, that LeeWay had not committed copyright infringement.

The complaint asks the court for the following:

· Declaration of No Valid Copyright

· Declaration of No Standing

· Declaration of No Copyright Infringement

· Declaration of No Unfair Competition

LeeWay Media also asks for attorneys’ fees and costs; and for a declaration that the claim of copyright infringement and unfair competition are in bad faith and, as such, should be sanctioned.

Practice Tip: In 1994, the Supreme Court addressed the issue of fee shifting in copyright cases in Fogerty v. Fantasy, Inc. Since then, the federal circuit courts have taken a variety of approaches to Fogerty and its statutory underpinning, 17 U.S.C. § 505. The Seventh Circuit is among the most willing of the circuits to shift fees, stating in Riviera Distributors, Inc. v. Jones, “Since Fogerty we have held that the prevailing party in copyright litigation is presumptively entitled to reimbursement of its attorneys’ fees.” This, perhaps, provides some insight into the rationale for a California plaintiff to sue citizens of California and New York in an Indiana court.

Eli Lilly Sues Perrigo for Patent Infringement of Axiron

Indianapolis, Ind. — Patent lawyers for Eli Lilly & Co. of Indianapolis, Ind. (“Lilly”), Eli Lilly  Export S.A., of Vernier/Geneva, Switzerland (a wholly owned subsidiary of Eli Lilly & Co.) and Acrux DDS Pty Ltd. of West Melbourne, Victoria, Australia (“Acrux”) filed a patent infringement suit alleging that Perrigo Company of Allegan, Mich. (“Perrigo Company”) and Perrigo Israel Pharmaceuticals Ltd. of Bnei Brak, Israel (“Perrigo Israel,” a wholly owned subsidiary of Perrigo Company), infringed Patent Nos. 8,435,944; 8,419,307; and 8,177,449, filed with the U.S. Patent Office.

Export S.A., of Vernier/Geneva, Switzerland (a wholly owned subsidiary of Eli Lilly & Co.) and Acrux DDS Pty Ltd. of West Melbourne, Victoria, Australia (“Acrux”) filed a patent infringement suit alleging that Perrigo Company of Allegan, Mich. (“Perrigo Company”) and Perrigo Israel Pharmaceuticals Ltd. of Bnei Brak, Israel (“Perrigo Israel,” a wholly owned subsidiary of Perrigo Company), infringed Patent Nos. 8,435,944; 8,419,307; and 8,177,449, filed with the U.S. Patent Office.

Lilly is engaged in the business of research, development, manufacture and sale of pharmaceutical products. Acrux is engaged in the development and commercialization of pharmaceutical products for sale. Both sell their products worldwide.

Lilly is engaged in the business of research, development, manufacture and sale of pharmaceutical products. Acrux is engaged in the development and commercialization of pharmaceutical products for sale. Both sell their products worldwide.

Perrigo Company and Perrigo Israel (collectively, “Perrigo”) are pharmaceutical companies that develop, manufacture, market and distribute generic pharmaceutical products for sale throughout the United States. These products include pharmaceuticals, infant formulas, nutritional products, dietary supplements and active pharmaceutical ingredients. Perrigo’s consumer-healthcare segment includes over 2,100 store-brand products which are marketed to major national chains such as Wal-Mart, CVS, Walgreens, Sam’s Club and Costco. They also sell to major drug wholesalers.

Lilly is the holder of approved New Drug Application No. 022504 for the manufacture and sale of a transdermal testosterone solution made at a concentration of 30 mg/1.5L, which is marketed by Lilly under the trade name “Axiron.” Axiron is a pharmaceutical drug which raises the amount of testosterone in a patient’s body. Recent sales of Axiron are estimated to be $229 million annually, according to Symphony Health Solutions. Axiron is subject to Patent Nos. 8,435,944, 8,419,307, 8,177,449 (the “‘944 patent,” the “‘307 patent,” and the “‘449” patent, respectively). All three patents have been licensed to Lilly.

Perrigo announced on May 29, 2013 that it had filed an Abbreviated New Drug Application (“ANDA”) with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (“FDA”) for approval of a generic version of Axiron. Prior to filing the ANDA, No. 204255, Perrigo sent a letter to Lilly to inform Lilly that “in Perrigo’s opinion and to the best of its knowledge, the ‘449 patent is invalid, unenforceable, and/or will not be infringed by the commercial manufacture, use, sale, or importation of the drug product described in Perrigo’s ANDA.” Perrigo sent similar letters regarding the ‘307 and ‘944 patents.

After receiving the letter, Lilly filed suit alleging infringement of the three patents. It states in its complaint that the ‘944 patent claims, inter alia, methods of increasing the testosterone blood level of an adult male by applying a transdermal drug-delivery composition that contains testosterone. The ‘307 patent includes in its claims a method of increasing the level of testosterone in the blood by applying a liquid pharmaceutical that contains testosterone. The claims for the ‘449 patent include a method of transdermal administration of a physiologically active agent. All three patents are used in connection with Axiron.

Lilly’s complaint lists the following claims:

· Count I for Patent Infringement (Direct Infringement of U.S. Patent No. 8,435,944)

· Count II for Patent Infringement (Inducement to Infringe U.S. Patent No. 8,435,944)

· Count III for Patent Infringement (Contributory Infringement of U.S. Patent No. 8,435,944)

· Count IV for Patent Infringement (Direct Infringement of U.S. Patent No. 8,419,307)

· Count V for Patent Infringement (Inducement to Infringe U.S. Patent No. 8,419,307)

· Count VI for Patent Infringement (Contributory Infringement of U.S. Patent No. 8,419,307)

· Count VII for Patent Infringement (Direct Infringement of U.S. Patent No. 8,177,449)

· Count VIII for Patent Infringement (Inducement to Infringe U.S. Patent No. 8,177,449)

· Count IX for Patent Infringement (Contributory Infringement of U.S. Patent No. 8,177,449)

· Count X for Declaratory Judgment (Infringement of U.S. Patent No. 8,435,944)

· Count XI for Declaratory Judgment (Infringement of U.S. Patent No. 8,419,307)

· Count XII for Declaratory Judgment (Infringement of U.S. Patent No. 8,177,449)

Lilly’s lawsuit asks for an injunction to stop Perrigo from producing the generic version of Axiron until the expiration of Lilly’s three patents-in-suit. In addition, Lilly asks that the court declare the three patents to be valid and enforceable; that Perrigo infringed upon all three by, inter alia, submitting ANDA No. 204255 to obtain approval to commercially manufacture, use, offer for sale, sell or import its generic version of the drug into the United States; that Perrigo’s threatened acts constitute infringement of the three patents; that FDA approval of Perrigo’s generic drug be effective no sooner than the expiration date of the patent that expires last; that this is an exceptional case; and for costs and attorneys’ fees.

Practice Tip: The FDA’s ANDA process for generic drugs has been abbreviated such that, in general, the generic drug seeking approval does not require pre-clinical (animal and in vitro) testing. Instead, the process focuses on establishing that the product is bioequivalent to the “innovator” drug that has already undergone the full approval process. The statute that created the abbreviated process, however, had also created some interesting issues with respect to the period of exclusivity. For an interesting look at some of these issues, see here.

Continue reading

Patent Trolls – A Growing Problem Receives National Attention

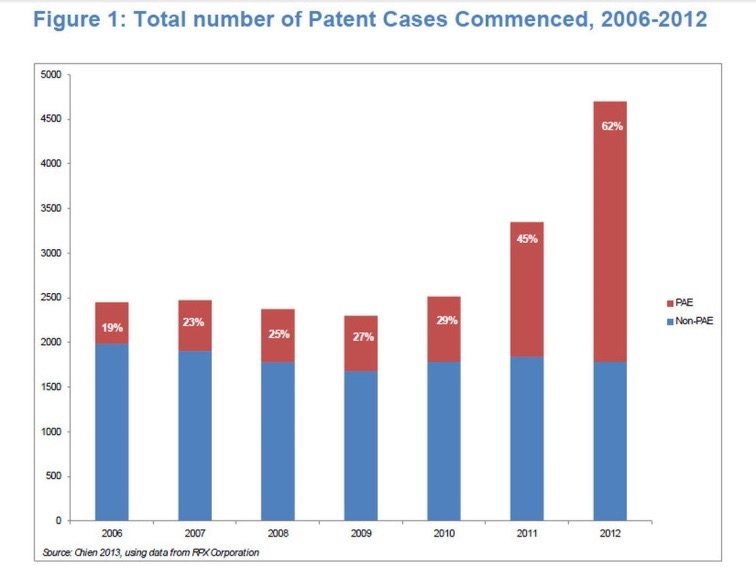

Litigation by patent-assertion entities (“PAEs,” commonly known as “patent trolls”) has skyrocketed in the last two years. A chart released by the White House in a June 2013 report entitled “Patent Assertion and U.S. Innovation” demonstrates that such trolls now file over 60% of all patent-infringement lawsuits. (The red portion of the bars shows patent lawsuits brought by PAEs.)

The patent-trolling business model includes no productive operations. Instead, investors’ money is used to purchase patents for the sole purpose of alleging infringement and extracting payment under the threat of litigation. Because litigation can be very costly, the patent trolls’ targets face a difficult decision: settle (typically by buying a license from the troll) or pay significant litigation expenses — and face the potential of losing at trial, which is somewhat unlikely but where damages can be enormous. In contrast, the trolls often use contingency-fee attorneys and, thus, have little more at stake in any given lawsuit than a few hundred dollars for a court-filing fee.

The patent-trolling business model includes no productive operations. Instead, investors’ money is used to purchase patents for the sole purpose of alleging infringement and extracting payment under the threat of litigation. Because litigation can be very costly, the patent trolls’ targets face a difficult decision: settle (typically by buying a license from the troll) or pay significant litigation expenses — and face the potential of losing at trial, which is somewhat unlikely but where damages can be enormous. In contrast, the trolls often use contingency-fee attorneys and, thus, have little more at stake in any given lawsuit than a few hundred dollars for a court-filing fee.

Many view this type of litigation with suspicion, if not outright derision. At least four patent-reform bills are pending in Congress and the Obama Administration recently released a harsh indictment detailing the damage to innovation and the economy caused by the “abusive practices in litigation” committed by patent trolls. Various measures to curb frivolous patent litigation have been suggested, including increasing transparency of patent ownership and establishing a website through the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office to inform patent-troll victims of their rights.

CordaRoy’s Originals Sues Lovesac for Infringement of Patented Bag-Bed Assembly

Evansville, Ind. — CordaRoy’s Originals, Inc. of Gainesville, Fla. (“CordaRoy’s”)  has sued The Lovesac Corporation of Stamford, Conn. (“Lovesac”) alleging infringement of Patent No. 7,131,157, “Bag Bed Assembly,” (the “‘157 Patent”) which has been issued by the U.S. Patent Office.

has sued The Lovesac Corporation of Stamford, Conn. (“Lovesac”) alleging infringement of Patent No. 7,131,157, “Bag Bed Assembly,” (the “‘157 Patent”) which has been issued by the U.S. Patent Office.

Patent lawyers for CordaRoy’s filed a patent infringement suit alleging that Lovesac has been and continues to infringe on CordaRoy’s ‘157 Patent for a bag-bed assembly by using, selling, offering to sell, and/or importing a “knock-off” bag-bed assembly which embodies the patented invention. It is also alleged that Lovesac has induced others to do likewise. CordaRoy’s asserts that the claimed infringement has been, and continues to be, intentional, willful and deliberate.

![]() In its complaint, CordaRoy’s asks for a judgment that the ‘157 Patent has been infringed; that Lovesac be required to account for all of its profits and advantages realized from the alleged infringement of the ‘157 Patent; for an award of lost profits and a reasonable royalty; for an award of treble damages upon a finding of willful, intentional, and deliberate infringement; for an injunction against further actions of infringement; for pre-judgment interest; and for costs and attorney’s fees.

In its complaint, CordaRoy’s asks for a judgment that the ‘157 Patent has been infringed; that Lovesac be required to account for all of its profits and advantages realized from the alleged infringement of the ‘157 Patent; for an award of lost profits and a reasonable royalty; for an award of treble damages upon a finding of willful, intentional, and deliberate infringement; for an injunction against further actions of infringement; for pre-judgment interest; and for costs and attorney’s fees.

A jury trial has been demanded.

Practice Tip: If a court finds that a patent has been infringed upon, it may then consider the additional issue of whether the infringement was willful. Infringing behavior that continued despite an allegation of infringement can support such a finding. The determination that an infringement was “willful” can, in turn, increase damages significantly.