[Disclosure: Overhauser Law Offices, LLC, the publisher of this website, represents a party in this litigation]

Chief Judge Philip P. Simon for the Northern District of Indiana has construed the claims of Patent No. 5,866,210, METHOD FOR COATING A SUBSTRATE.

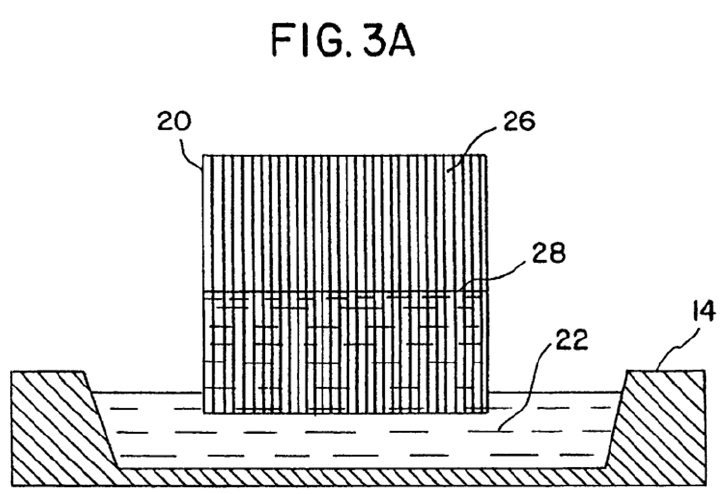

The ‘210 patent describes a method of coating substrates such as those used in catalytic converters. Catalytic converters are typically found in automobile and truck engines, and their purpose is to reduce or remove harmful emissions from engine exhaust. The type of catalytic converter relevant here is principally composed of a core – or substrate – which sits inside a metal housing. The substrate is a single unit (a monolithic substrate) that has a number of honeycomb-like channels running parallel to each other within the metal frame. Through various methods, the inner walls of these channels are coated with a catalyst slurry made of precious metals. As engine exhaust flows through the substrate’s channels, the precious metals coating the channels’ inner walls cause a chemical reaction that converts the harmful engine emissions into more benign substances. But because the precious metals are expensive, care must be taken to sufficiently coat the channels without wasting the catalytic slurry.

The ‘210 patent teaches a method of coating the channels of the substrate through a process called vacuum infusion coating. Through this process, one end of the substrate is partially immersed in a dip pan of catalytic slurry. The dip pan, the size and depth of which may vary, is loaded with an amount of slurry exceeding the amount of coating necessary to coat the walls of the substrate to a desired level. A vacuum is applied to the other end of the substrate, which draws the slurry of precious metals up the channels of the substrate to coat the inner walls of the substrate’s channels. The vacuum continues to suck air through the channels as the substrate is removed from the pan, and then the coating dries to the channel walls. The ‘210 patent teaches that each of the channels of the substrate are coated to the same length, creating a “uniform coating profile.” And as the specification explains, “the typical coating operation requires the immersion of one end of the substrate into the coating media followed by drying and then the insertion of the opposed end of the substrate into the coating media followed by drying and curing.”

of coating the channels of the substrate through a process called vacuum infusion coating. Through this process, one end of the substrate is partially immersed in a dip pan of catalytic slurry. The dip pan, the size and depth of which may vary, is loaded with an amount of slurry exceeding the amount of coating necessary to coat the walls of the substrate to a desired level. A vacuum is applied to the other end of the substrate, which draws the slurry of precious metals up the channels of the substrate to coat the inner walls of the substrate’s channels. The vacuum continues to suck air through the channels as the substrate is removed from the pan, and then the coating dries to the channel walls. The ‘210 patent teaches that each of the channels of the substrate are coated to the same length, creating a “uniform coating profile.” And as the specification explains, “the typical coating operation requires the immersion of one end of the substrate into the coating media followed by drying and then the insertion of the opposed end of the substrate into the coating media followed by drying and curing.”

The Court’s ruling on claim terms proposed by patent attorneys for the parties were as follows:

“Uniform Coding Profile” – the substrate is coated by the slurry to approximately the same length across the channels so that the profile deviates only slightly, if at all, across the width of the substrate.

“Into each of the channels for a distance which is less than the length of the channels to form a uniform coating profile” – this term has a “normal, ordinary meaning” and therefore needs no construction.

“Said vessel containing an amount of coating material in excess of the amount sufficient to coat the substrate to a desired level” -a vessel containing more slurry than is needed to coat the channels less than the length of the substrate, such that the height of this slurry above the bottom of the immersed substrate is high enough above the immersed end during coating that no air is drawn in the channels.

“At an intensity and time sufficient to the coating media upwardly from the bath” – This term has a normal, ordinary meaning that does not require construction. (The argument of Aristo’s patent lawyers that “an intensity and time sufficient “was indefinite and thus invalid, was rejected.)

“Replenishing the bath with an amount of the coating media which was used to coat the substrate” and “while the substrate is being coated” – these phrases have a normal, ordinary meaning and need not be construed.

“A coated monolithic substrate having a uniform coating profile produced in accordance with the method of claim 1” – This phrase has a plain and ordinary meaning and does not require construction.Opinion Basf v Aristo

Indiana Intellectual Property Law News

Indiana Intellectual Property Law News