Washington, D.C. – While unanimously agreeing that induced patent infringement liability requires knowledge that the induced acts will infringe one or more patents, the United States Supreme Court, in an 8-1 decision in the Global-Tech Appliances, Inc., v. SEB S.A. case, held that the knowledge requirement is met by “willful blindness.”

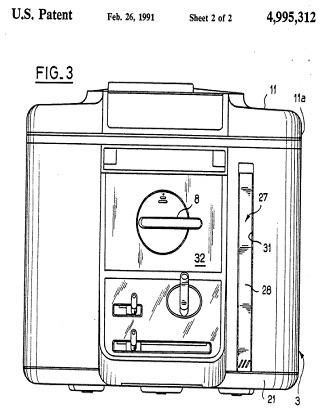

SEB S.A. is a French company specializing in home-cooking appliances. The inventor of a home-use deep fryer with external surfaces that remain cool during the frying process, SEB holds Patent No. 4,995,312, as issued by the U.S. Patent Office, for a Cooking Appliance with Electric Heating. Global-Tech Appliances, Inc. (now known as Global-Tech Advanced Innovations Inc.) is a British Virgin Islands corporation. Global-Tech subsidiary Pentalpha Enterprises, Ltd. supplied Sunbeam Products, Inc. (a U. S. competitor of SEB) with certain deep fryers having all but the cosmetic features of the patented SEB fryer. Shortly after agreeing to supply Sunbeam, Pentalpha retained an attorney to conduct a right-to-use analysis, but did not inform him that their product was based on the SEB product, and the attorney did not locate the ‘312 patent during prior art searching.

SEB S.A. is a French company specializing in home-cooking appliances. The inventor of a home-use deep fryer with external surfaces that remain cool during the frying process, SEB holds Patent No. 4,995,312, as issued by the U.S. Patent Office, for a Cooking Appliance with Electric Heating. Global-Tech Appliances, Inc. (now known as Global-Tech Advanced Innovations Inc.) is a British Virgin Islands corporation. Global-Tech subsidiary Pentalpha Enterprises, Ltd. supplied Sunbeam Products, Inc. (a U. S. competitor of SEB) with certain deep fryers having all but the cosmetic features of the patented SEB fryer. Shortly after agreeing to supply Sunbeam, Pentalpha retained an attorney to conduct a right-to-use analysis, but did not inform him that their product was based on the SEB product, and the attorney did not locate the ‘312 patent during prior art searching.

Previously in this case, a jury found that Pentalpha directly infringed the ‘312 patent and willfully induced others to infringe the patent. On an appellate challenge to the induced infringement judgment, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit held that “deliberate indifference” of known risks is a form of actual knowledge and the evidence supported the conclusion that Pentalpha deliberately disregarded a known risk that SEB held a patent covering its deep fryer.

Under 35 U.S.C. § 271(b), “[w]hoever actively induces infringement of a patent shall be liable as an infringer.” Justice Alito, writing for the Supreme Court, opined that, while not expressly stated, an intent requirement arises from the “actively induces” language in this statute. However, the Court rejected the Federal Circuit’s “deliberate indifference” standard for intent.

As an initial matter, the Court found its decision in Aro Mfg. Co. v. Convertible Top Replacement Co., 377 U. S. 476 (1964) as applicable precedent, despite characterizing it as a “a badly fractured decision.” In that case, the Court found contributory infringement under 35 U.S.C. § 271(c) required that an infringer “must know that the combination for which his component was especially designed was both patented and infringing.” Thus, the Court held in the present case that, as with the concept of contributory infringement, inducement of infringement requires that the accused party know the induced act(s) constitute infringement.

With regard to what constitutes sufficient knowledge, the Court interestingly noted the long-standing willful blindness standard in criminal law and stated “we can see no reason why the doctrine should not apply in civil lawsuits for induced patent infringement under 35 U.S.C. § 271(b).” The Court then identified the two requirements for willful blindness: (1) the defendant must subjectively believe that there is a high probability that a fact exists, and (2) the defendant must take deliberate actions to avoid learning of that fact. The Court found that even the willful blindness approach to risk knowledge was met in this case, with “the evidence … more than sufficient for a jury to find that Pentalpha subjectively believed there was a high probability that SEB’s fryer was patented, that Pentalpha took deliberate steps to avoid knowing that fact, and that it therefore willfully blinded itself to the infringing nature of Sunbeam’s sales.”

PRACTICE TIP: Showing that an infringement-inducing defendant appreciated a high probability of infringement is a subjective issue and not easily proved. In this regard, the Court’s opinion increases the burden on patentees attempting to enforce their rights.

Indiana Intellectual Property Law News

Indiana Intellectual Property Law News